Opinion

Tears for Sixena

“It was a pile of burnt rubble [...]. I ran through the ruins of the old cloister to head towards the famous 12th century chapter house: I could not hold back my tears in front of the ashes of one of the most beautiful monuments in the world”: This is how the art historian and architect Josep Gudiol i Ricart (1904-1985) remembered the astonishing vision of this space of the Royal Monastery of Santa Maria de Sixena when he arrived there, probably in mid-October 1936, and found it burnt and half-ruined, due to the fire it had suffered at the end of July of that same year, a few days after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

Thus began a long history of saving an exceptional artistic heritage, which, many years later, would end up harshly confronting Catalonia and Aragon, or, at least, a significant sector of their political representatives and institutions and people from their artistic, heritage and cultural world.

A royally founded monastery

The Royal Monastery of Santa María de Sixena (or Sijena, in Spanish), is located in the town of Villanueva de Sijena, in the province of Huesca (Aragon), in the heart of the Monegros region. The imposing Romanesque monastery was founded in 1118 by Queen Sança de Castellà, wife of Alfonso the Chaste, King of Aragon and Count of Barcelona. She and her son Peter the Catholic, also King of Aragon and Count of Barcelona, were also buried there, making it a royal pantheon.

The ownership and administration of the monastery would be granted to the female branch of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, whose members would tend to be members of the nobility and wealthy classes of the territory. However, from an ecclesiastical point of view, and despite being located in Aragon, the monastery would depend until 1995 on the bishopric of Lleida, a fact that is important to remember in this whole affair.

The link and protection with the royal family would grant an important temporal domain to the monastery. A wealth, and also a power, great and disproportionate, which, during the 12th-14th centuries, would find echo in the architecture of the monastery and in its artistic treasure. However, from the end of the 15th century, a slow and progressive process of decline of the monastery would begin, which would be accentuated in the 19th century, with the confiscation of ecclesiastical property implemented throughout the Spanish state.

Despite the declaration of a national monument, made in 1923, the contributions it would receive from the state for its conservation would be very meager, and the architecture of the complex would suffer. Stripped of the substantial income and donations that it had had in the first centuries of its history, the comfort of convent life would suffer. And, at least from the 18th century, the recurring sale of works of art would become a palliative for the needs of the monastery. The definitive blow to its survival, however, would not come until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, in 1936.

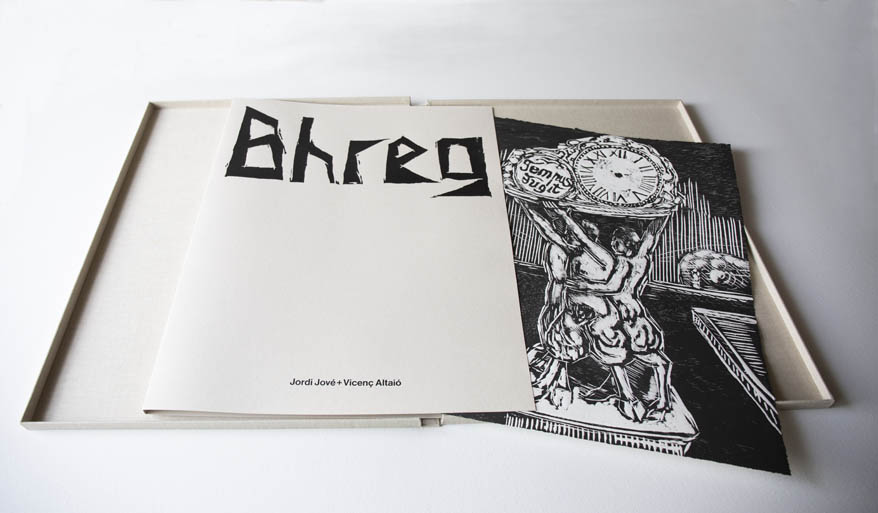

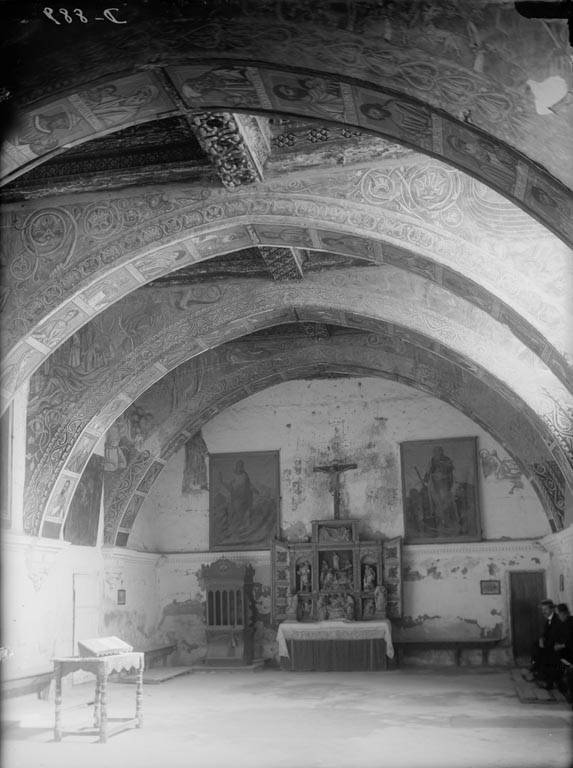

Sala capitular del Monestir de Santa Maria de Sixena, abans de l'incendi.

Sala capitular del Monestir de Santa Maria de Sixena, abans de l'incendi.

The monastery fire during the Spanish Civil War

Several oral and written testimonies place the date of the tragic fire around July 25, 1936. Without reliable evidence, it has been customary in Aragon to attribute the mischief to militiamen from Catalonia, who, indirectly, would have been under the orders of the president of the Generalitat, Lluís Companys. However, some recent historical studies, based on more reliable documentary evidence, allow us to hypothesize that it was caused by inhabitants of the town, especially members of the local anti-fascist committee, with the collaboration of other evildoers from outside, whose link to Catalonia cannot be proven.

In any case, the fire, and the looting that would accompany it, would seriously affect the monastery, which, it should be remembered, had already been suffering from a significant process of degradation for some time. The fire would especially affect the large chapter house of the monastery, covered with magnificent Mudejar coffered ceilings and exhaustively decorated with rich pictorial iconography, which covered both the arches and the walls of the room.

In fact, in the face of the complete destruction, Josep Gudiol had reason to cry, since he knew the burnt paintings and their extraordinary artistic and cultural value well. It was not for nothing that, at the end of February and the beginning of March 1936, together with the photographer Antoni Robert (1903-1976), he had visited the monastery and had carried out an exhaustive work of photographic documentation. Thanks to this documentation, today we can better know and appreciate both the scope and quality of the burnt paintings and the entirety of their iconographic repertoire.

A "Sistine Chapel" of the Romanesque art of the Iberian Peninsula

Some art historians, referring to the chapter house of the Sixena monastery, have gone so far as to describe it as the "Sistine Chapel" of Romanesque art in the Iberian Peninsula, such was the extent, exuberance, and beauty of the pictorial cycle that was displayed there before the fire.

Thus, before the fire, scenes from the Old and New Testaments alternated in all the arches of the hall. The episodes of the former were arranged in the niches of the arches of the diaphragm, and, among other scenes, recreated the creation of Adam and Eve, their expulsion from Paradise, the death of Abel at the hands of Cain, and other themes taken from the history of Noah, Isaac and Moses. On the other hand, on the perimeter walls of the space a cycle on the life of Christ was also displayed, which began on the north wall, with scenes of the Nativity. Finally, on the soffits of the arches, the series of genealogies of Christ also appeared, which symbolically connected the Old and New Testaments. And this entire splendid ensemble was covered by an extraordinary Mudejar coffered ceiling, which, in itself, also constituted a work of art.

Art historians who have studied the paintings note the courtly taste of the paintings, with a special taste for detail, profusion and a strong sense of color, all of which are very characteristic features of the art of the 1200s. Currently, its authorship is attributed to one of the so-called "Master of the Sixena Chapter House", and its execution is usually dated between 1196 and 1208. For anyone who wants to deepen their knowledge, I recommend the extraordinary study made by Montserrat Parés Paretas, in her book "Sacred and Profane Mural Painting, from Romanesque to Early Gothic" (Montserrat Abbey publications, 2012).

Unfortunately, the fire would severely damage the whole. Thus, to begin with, the extraordinary coffered ceiling that covered the room was lost and a good part of the wall paintings were completely destroyed. Those that were saved, which some estimate to be around 32% of the original work, were also badly damaged. The fire also altered the original tones of the paintings, originally bright and predominantly blue, with the exception of those located in the last of the four lateral arches communicating with the cloister, which, miraculously, were saved from the flames as this arch was walled up at the time of the fire.

Sala capitular del Monestir de Santa Maria de Sixena, després de l'incendi (1936)

Sala capitular del Monestir de Santa Maria de Sixena, després de l'incendi (1936)

The rescue and transfer of the paintings

Before the tragic fire, as the historian Guillem Cañameras Vall points out in an interesting article (Bulletin of the Catalan Society of Historical Studies, XXVIII, 2017), Josep Gudiol had already made clear his concern about the state of the paintings and the process of degradation that affected them, and had conveyed his concern to other Catalan historians and art lovers. Thus, just two months before the tragedy, Gudiol had guided a visit to the monastery of the Friends of the Museums of Catalonia association, where attendees had been able to verify the foundation of their guide's concerns during this visit.

As a result of this visit, the Catalan art historian Joaquim Folch i Torres would also publish a review of it in La Vanguardia on July 2 of the same year, where, referring to the mural cycle of the chapter house, he stated: "we could see, with pain, how the destruction of the mural paintings of its beautiful chapter house is progressing in an alarming manner", also adding that "the work is lost and will be lost completely, if those who can and must not come to save it", that is, the Aragonese and state artistic authorities.

It seems that the news of the monastery fire had a great impact on Josep Gudiol and he decided to intervene. Thus, from various sources, we know that a few days after learning of the tragedy, he had already begun to imagine the possibility of tearing out what remained of the paintings to guarantee their conservation. It is not for nothing that, since July 23, 1936, he was part of the Committee for the Salvation of Artistic Heritage that the Generalitat of Catalonia had created to protect the country's archaeological and artistic heritage, both public and private, threatened by the revolutionary storm.

However, it seems that it would not be until Gudiol's new trip to the monastery on 15 and 17 October 1936 that he would definitively see the imperative and unpostponable need to proceed with its demolition. To do so, he would need to quickly find funding. And this would come precisely from the 4,000 pesetas of the time that, between 18 and 23 October, he would obtain from the Generalitat of Catalonia.

Thanks to the support of the Catalan Government, the demolition work, led by Gudiol, would take place between October 24 and November 6 of the same year, in just fourteen days of work. Luck would be with them, since until the last day of work, as Gudiol himself would explain, it would not rain, preventing the paintings in the monastery's chapter house from getting wet, which, since the fire, no longer had a roof.

Primeres intervencions d'arrencaments de les obres al monestir de Sixena (1936)

Primeres intervencions d'arrencaments de les obres al monestir de Sixena (1936)

The restoration and public exhibition of the paintings in Barcelona

Torn using the strappo technique, the same one that had been used decades earlier to transfer Romanesque paintings from various churches in the Pyrenees onto canvas, the Sixena paintings were transferred to Barcelona on 8 November and deposited in the improvised restoration workshop on behalf of the Monuments Service of the Generalitat in the Ametller house in that city. They would remain there until 5 August 1939, when they were transferred again to the National Palace of Montjuïc.

In 1943, the paintings would return to the laboratory of the Ametller house to be restored by Gudiol himself, and, a year later, they would begin to be mounted on wooden structures. The restoration would be paid for by the Barcelona City Council, as the state's Directorate General of Fine Arts had declined to provide the necessary funds. Finally, in 1949, the paintings would return to the Museu d'Art de Catalunya with the aim of being exhibited publicly.

Still in the late 1950s, the director of this museum Joan Ainaud de Lasarte (1919-1995) would promote the rescue of some fragments of painting that were still in the monastery, especially those found on the south wall of the chapter house, in the arch that connected with the cloister, which preserved the original colors intact, because this space was walled up at the time of the fire. The operation would have the approval of the Sant Joaniste nuns and the Francoist authorities of the time. Once again it would be an act of legal and authorized safeguarding, and not of plunder.

The diaspora of the Saint John nuns and their heritage

As a result of the events of 1936, the community of Saint John nuns of Sixena would abandon the monastery and three years later, in 1939, would settle in the hermitage of Butsènit, near Lleida, under the protection of their bishop. A significant part of the artistic heritage of the monastery would also travel with the nuns. It seems that the community would not return to the monastery until 1946, once minimal conditions of habitability had been restored. As for the artistic treasure of the monastery, some would return with the nuns, while the rest would remain on deposit in the Diocesan Museum of Lleida, and, for documentation, in the provincial archive of Huesca.

However, and during the following decades, the monastery would not be able to recover: weakened in terms of members and resources, the Sixena community would definitively abandon the monastery in 1970, and would move to Barcelona, to integrate into the convent that the order had in that city, in Sant Gervasi de Cassoles. A significant part of the monastery's artistic heritage, however, would remain on deposit in the Diocesan Museum of Lleida, property of the bishopric to which the monastery belonged ecclesiastically. Also, in 1972, they left deposited in the Museum of Art of Catalonia several objects and works of art, most of them small in size and of relative artistic value.

Later, in 1977, the nuns of both communities, that is, of Sixena and Barcelona, already merged into one, would move again to the monastery of Our Lady of Alguaire and Sant Joan de Jerusalem in Vallparadís, near Terrassa, to a new building, the work of the Catalan architect Jordi Bonet i Armengol (1925-2022).

It was also during these years that the three sales made to the Generalitat of Catalonia of the heritage owned by the community that had previously been deposited in the Episcopal Museum of Lleida and the Art Museum of Catalonia were formalized, the respective contracts for which would be signed in 1982 and 1993, respectively, for a total value of 50,000,000 pesetas, and that the permanent deposit of the paintings in the aforementioned Barcelona museum would also be agreed upon, which, from 1990, and due to the Law on Museums of Catalonia, would change its name to the National Art Museum of Catalonia (MNAC).

Despite the financial resources obtained from the sale of its assets, the life of the new convent of Saint John of Valldoreix would also be short-lived: lacking vocations and noticeably diminished by the aging and death of the nuns, its small community would again be forced to close the house and move, in 2007, to another convent of the order, this time the monastery of Saint John of Acre, in Salinas de Añana (Gesaltza-Añana, Álava), in the Basque Country. A few years later, a nun from there, Sister Virgína Calatayud, seems to have obtained from the Vatican papal authorization to represent all the Spanish monasteries of the order. In the long run, as we will see later, this fact would become lethal for the interests of the MNAC and Catalonia.

Pintures de la sala capitular del monestir de Sixena conservades al MNAC.

Pintures de la sala capitular del monestir de Sixena conservades al MNAC.

The long cultural war over the heritage of the Franja and Sixena

On 18 February 2014, the Government of Aragon filed a lawsuit before the Court of First Instance of Huesca for the mural paintings in the Sixena chapter house to be reinstated in the monastery. This lawsuit would be one of the numerous legal actions implemented by the Aragonese government since 1997, many of them with the support of the Vilanova de Sixena City Council as an interested party, in which they demanded not only the declaration of nullity of the purchases of artistic assets from the Sixena monastery that the Generalitat of Catalonia had made in 1983 and 1992, but also the return of the paintings from the old chapter house of this monastery, which, since the 1940s, had been in legal deposit at the MNAC.

On the other hand, the legal actions implemented by the Aragonese institutions for the sake of the artistic treasure of Sixena, were added to the lawsuit that the Aragonese bishopric of Barbaste-Montsó had open with the bishopric and the Consortium of the Museum of Lleida, for the ownership of one hundred and eleven works of art from various parishes of the Franja de Ponent that were in this museum, most of which came from purchases, exchanges, deposits and donations made by the diocese of Lleida. The reason alleged was that these works of art came from the Aragonese parishes, which until 1995 belonged to the bishopric of Lleida and since then, by decision of the Vatican, had become ecclesiastically dependent on the bishopric of Barbaste-Montsó.

As Francesc Canosa explains very well in his very interesting book Sixena. La croada de la memória (Editorial Fonoll, 2018), it would be precisely this Vatican decision, in which it seems that the Spanish Episcopal Conference and Opus Dei would have played a very decisive driving role, that would spark the conflict, which, beyond a dispute between bishoprics, would soon take the form of a bloody cultural war between Aragon and Catalonia.

The trial for the ownership of the Sixena paintings would be held in the Huesca court of first instance on January 18, 2016. The Aragonese side would present the action of removing the paintings carried out by Josep Gudiol as a true "looting", while the Catalan side, in the words of Pepe Serra, director of the MNAC, justified and defended it as a "heroic act" and a rescue operation.

Escena d'un àngel ensenyant a cavar a Adán, abans i després de l'incendi. Arxiu LV/MNAC

Escena d'un àngel ensenyant a cavar a Adán, abans i després de l'incendi. Arxiu LV/MNAC

During the trial, and at the request of the MNAC, reports would be presented and several experts would also appear to defend the need for the pieces to remain at the MNAC and warn of the risks of their transfer. Among them would be the report of Gianluigi Colalucci, restorer of the paintings of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, and who, before his death in 2021, was considered the world's greatest authority on mural painting. However, to the surprise and irritation of the Catalan parties, the judge in the case went so far as to question the rescue work carried out by Gudiol in Sixena and, without any concern for the safety and future conservation of the paintings, ruled in favor of the Aragonese claim.

The Catalan party would appeal the judge's decision to higher judicial bodies, up to the Supreme Court, but without any success. As the recent ruling of this latter court, dated May 27, 2025, indicates, the paintings are the property of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, represented by the nun Virginia Calatayud, of the convent of Salinas de Añana, who, in 2013 and in her capacity as Pontifical Commissioner, would have ceded to the Aragonese government the right to act on behalf of the order to lift the deposit of the paintings made at the MNAC and request their return to the monastery of Sixena.

Before that, however, the Generalitat de Catalunya, the MNAC, the Bishopric of Lleida and the Consortium of the Museum of Lleida would also lose the rest of the demands presented by the Aragonese side, with disastrous consequences for both museums. Thus, the court order to return the works of art kept in the Museum of Lleida without delay would lead to the absurd occupation of the museum on the night of November 11, 2017, and the departure, "manu militari", of them towards Aragon, amidst the clamor and protest of the people of Lleida and of so many other people from all over the country who went to protest there. All of this happened, it is worth remembering, in full application of article 155 of the Constitution, suspending Catalan autonomy, and without the Spanish state doing anything to prevent it.

Finally, in 2021, in a new episode of defeat and surrender for our country, the Lleida Museum consortium would deliver, this time without any resistance, to the bishopric of Barbastre-Montsó the one hundred and eleven works of art from the parishes of the Strip, which this bishopric had been claiming for years.

Despite not being a lawyer, reading all these rulings surprises and horrifies me for their stench of interested bias, lack of basis for certain arguments and evidence, and, above all, for the absence of any historical consideration, much less museum and heritage considerations. It seems, therefore, that what is important for the judges is to settle ownership, and not to guarantee the integrity and correct conservation of an exceptional artistic heritage.

Les caixes sepulcrals del Museu de Lleida ara exhibides al Monestir de Santa Maria de Sixena.

Les caixes sepulcrals del Museu de Lleida ara exhibides al Monestir de Santa Maria de Sixena.

And now what?

Diplomacy has played no role in this cultural war. Beyond a timid attempt by Minister Santi Vila in 2016, which no one in Catalonia understood or supported, none of the interested parties, not even the Ministry of Culture itself, have done anything throughout this almost twenty-seven year conflict to establish a dialogue and seek agreed solutions.

On the other hand, the positioning of more technical bodies, both at the state and international level, such as ICOM itself (International Council of Museums), has not been very shameful or courageous, considering that what is being harmed are two museums, which historically have legitimately constituted their collections, and that this process has not violated any ethical or moral norm. Here we are not talking about spoils of war or decolonization, on the contrary, we are talking about safeguarding and conserving the heritage and the integration of two museum collections.

Surely, the Aragonese attitude would not have made any dialogue or pact or compromise solution possible either. For the Aragonese executive, and probably also for most of the political forces in the region, the only possibility was to win and defeat Catalonia, at any cost: a powerful argument, often steeped in Catalanophobia, which, both in Aragon and in other territories of the Spanish state, seems to currently yield a lot of electoral returns. It should not be forgotten that any cultural war is, first of all, essentially of an identity nature, and, by extension, political.

In the face of all this, the attitude of the Department of Culture of the Generalitat, and, by extension, of the entire Catalan Government, has been, once again, evasive and escapist. Leaving aside the grandiloquent rhetoric, the argument has been the same as always: respect for the decision of the judges and compliance with the law. In addition to the fact that in Madrid there is now "a friendly government", and it is better not to disagree, we have already seen what happened to the former ministers Santi Vila and Lluís Puig for not being obedient.

Detall de les pintures de la sala capitular del monestir de Sixena conservades al MNAC.

Detall de les pintures de la sala capitular del monestir de Sixena conservades al MNAC.

The hot potato, then, has been transferred to the MNAC Consortium (where in addition to the Generalitat, the Barcelona City Council and the Ministry of Culture are also represented), but this does not seem entirely true to me: to whom the problem has really been transferred is to the director and the technicians and techniques of preventive conservation and restoration of the museum. They are now the last bulwark of containment against the irrationality and barbarity of justice. They are the Joseps Gudiols of our days.

And the fact is that the degree of fragility of the Sixena mural paintings exhibited at the MNAC is very high. All the national, state and international experts consulted, except for a small handful of Aragonese technicians, agree on this fact. A new movement and a forced installation in a space without the guarantees of correct preventive conservation assured will be lethal for them. On the other hand, in the restoration process carried out by Gudiol, there were alterations to the size and format of the paintings, which, in the opinion of these experts, make it impossible for them to fit into the original space of the monastery's chapter house. Unless you want to pull the trigger, scissors and hammer in hand.

Seeing how things have gone so far, with the judges' lack of sensitivity and concern for the conservation of heritage, I am not very optimistic about the outcome of the story. Perhaps the restorers of the MNAC will be brave and make a conscientious objection to this savagery, and refuse to perpetrate it. However, we cannot expect it, we cannot demand it from them. Thus, the most likely thing is that we will see another entry into the MNAC, more or less militarized or judicialized, of technicians appointed by the Aragon government to take the paintings, at any price, and this in the face of the passivity of our institutions.

Faced with this sad panorama, a cruel irony of history, it is possible that many of us will cry, just as, eighty-nine years ago, Josep Gudiol cried when he saw the destruction done to the paintings he had photographed. And they will again be tears of rage, of indignation, of impotence. Yes, tears for Sixena.

Postscript . It will be interesting to see what the Spanish Ministry of Culture, which is now silent and turning its head, will allege when they are asked again to move Picasso's Gernika to the Basque Country, or to return the Lady of Elche to the Valencian Country, or the Costitx bulls to Mallorca: that there are expert reports that assure that the works cannot be moved? Wow...