Exhibitions

Joan Miró and the Orant de Pedret, meeting point: Solsona

The sympathy between Joan Miró and the most archaic Catalan Romanesque in a temporary exhibition at the Diocesan Museum of Solsona.

The exhibition The Praying Man and Miró. Mural Spirit, which can be visited at the Diocesan Museum of Solsona until July 2025, is one of those very strange cases in which the cards —the facts— are so good that they play off each other. without having to alter anything much. When this happens, the most difficult thing is precisely not to spoil it by overloading a reality with meanings that perhaps does not allow it. But there is also another explanation: that this feeling of perfect consonance between the events is only the result of a well-crafted illusion by the creators, in this case, of the exhibition, who would then deserve a double round of applause.

Maqueta mural Lluna, Miró. © Succession Miró

Maqueta mural Lluna, Miró. © Succession Miró

In 1937, a set of pre-Romanesque paintings was discovered in the Church of Sant Quirze de Pedret, Cercs, hidden under a later layer of equally Romanesque but much later images. Although the interest in the other works should not be discounted, of the entire oldest set, one image with a singular magnetism stands out: the Orant de Pedret, by which name it is known.

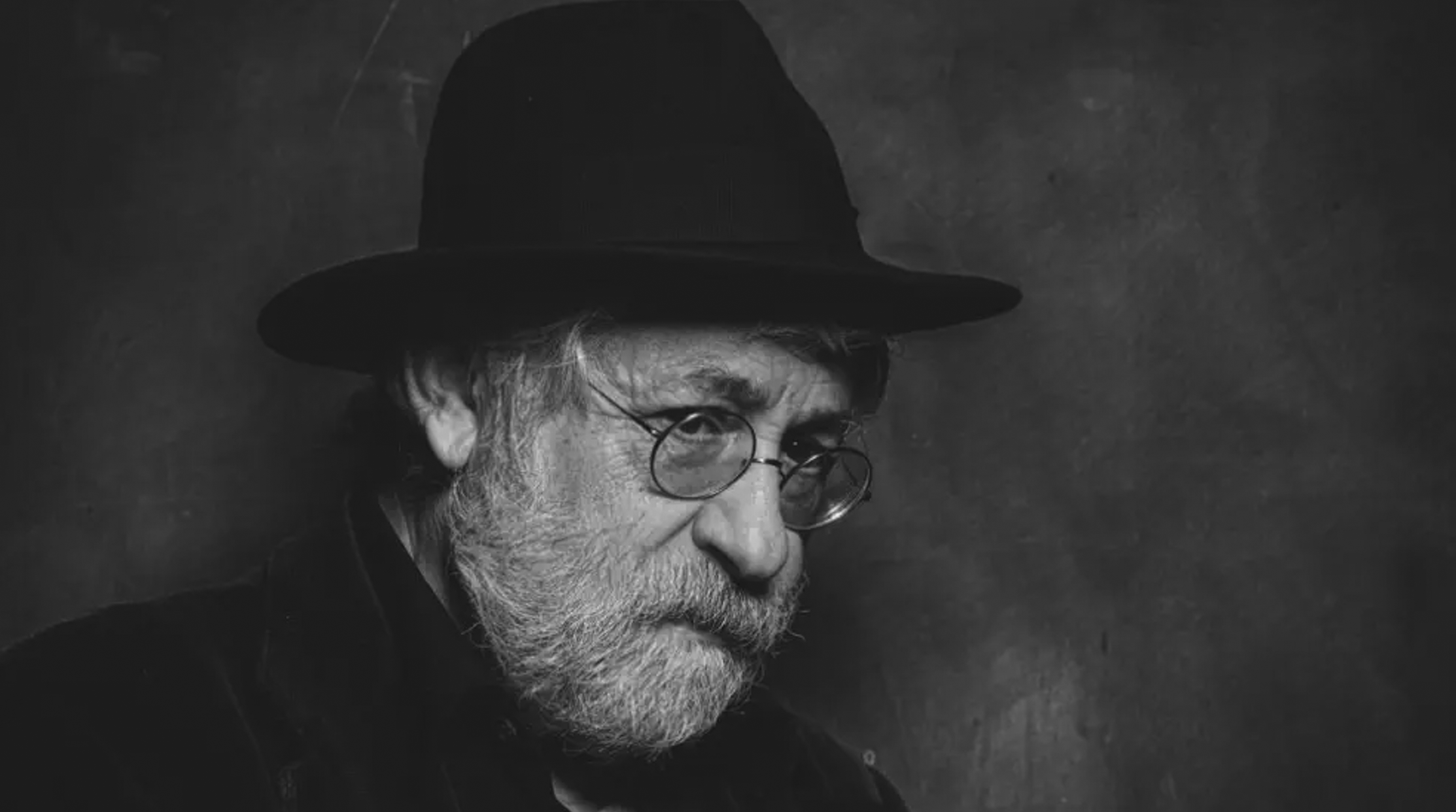

The image, which represents a male figure with outstretched arms inscribed within a circle and crowned by a bird, was contemplated (and we deduce that celebrated) by Joan Miró during a visit to the museum in 1951. Later —or earlier, as you will see, this will be part of the charm— he turned it into a central stimulus when creating; this was discovered by Marta Ricart, curator of the exhibition, with the identification of several reproductions of the Orant in the artist's different workshops and in the Miró Foundation archive.

Miró al Museu de Solsona davant Orant de Pedret, 1951. © Col·lecció Tormo Ballester

Miró al Museu de Solsona davant Orant de Pedret, 1951. © Col·lecció Tormo Ballester

Therefore, the visitor who arrives in Solsona and, before or after seeing the permanent collection, enters the small room where this dialogue has been structured, will have everything in his favor —we won't say: chewed— to naturally understand the way in which these two mentalities are different but similar. The Romanesque character gives off an enigmatic grace that is, in a different sense, shared by experts: the hypotheses about the symbology of that old icon do not seem to agree. In early Christian art it is common to find people in a position of prayer, praying, but they are represented with their arms slightly bent upwards; some believe that our character is too rustic (in the worst sense) to have joints, but, nevertheless, the horse next to him enjoys well-muscled thighs that do not suffer from this condition. Then, our thoughts move us to the outline of the cross —visual foundation of Christianity—, but that living man (we know this from his colored cheeks) does not seem to have anything to do with the crucified Christ. And although the interest in this case is not ornithology, let me say that the bird that has sometimes been identified as a royal peacock —although of multiple symbolism, often a bird of paradise— does not make it clear that it is either, unlike its companion that does show the characteristic crest and long tail. The temptations to theorize and counterargue, as you can see, could be infinite: this is one of the particularities of the great works that Orant accomplishes; along with that of being a source of inspiration and artistic fecundity, which is the reaction that —only perhaps— Joan Miró produced.

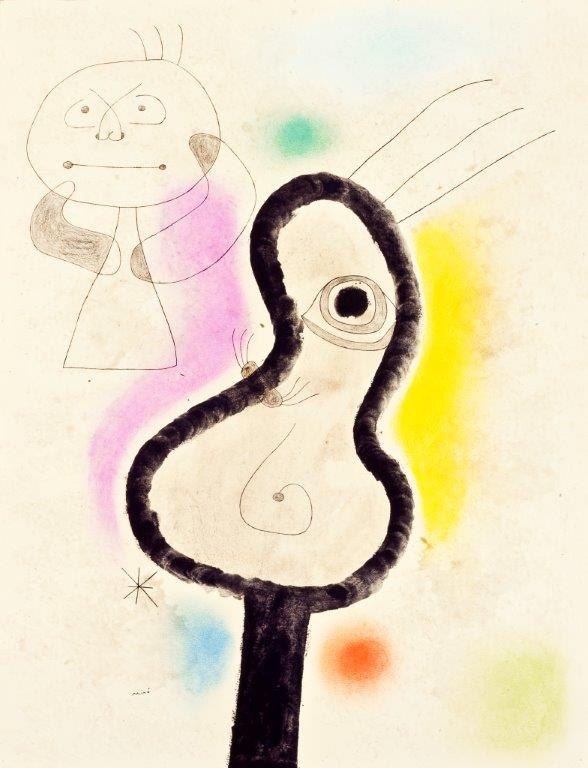

Personatge, ocell, estel, Joan Miró (1943). © Fundació Joan Miró

Personatge, ocell, estel, Joan Miró (1943). © Fundació Joan Miró

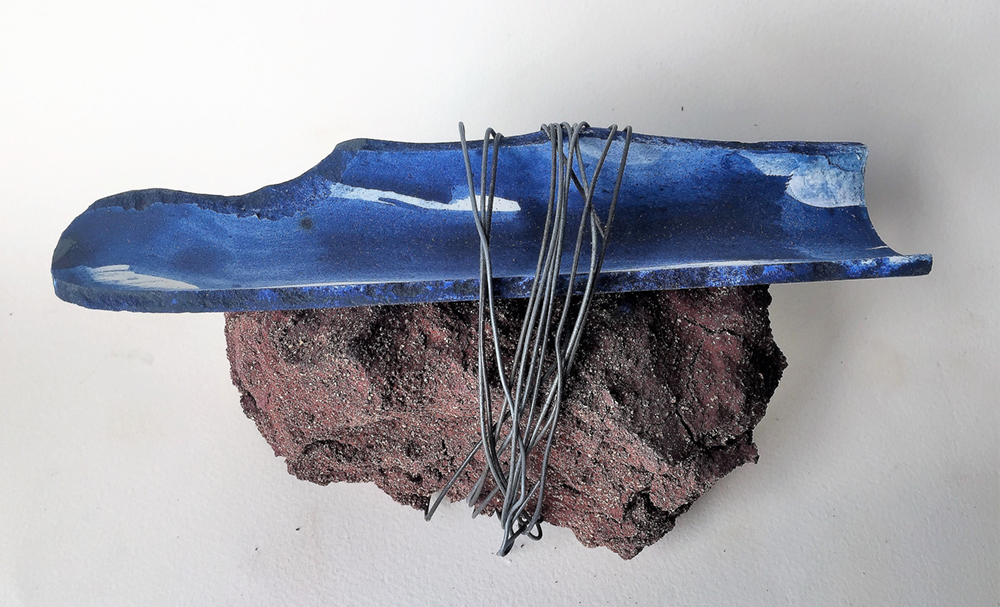

Although in a very different way, characters with birds had been appearing in Miró's works for some time before this direct encounter with Pedret's. However, as is hinted at in Solsona by exhibiting one of the multiple versions of Dona i ocell (1968), the way in which this combination of character and bird will reappear in the form of drawings or sculptures in Miró's work in the following years comes a little closer to the composition of the Romanesque fresco. We admit that once Pedret's character has entered our memory it is impossible not to look for him further, but it would not be at all strange if the same thing had happened to the artist. In any case, the room texts include an excellently chosen phrase by Miró that makes us think that, on his part, the play with tradition is sought: “After this pilgrimage to the sources of our art, we wanted to place ourselves under the sign and invocation of the Catalan Romanesque artists and Gaudí.”

As Marta Ricart says, in Orant Miró must have found “a confirmation of his spiritual and political ideas”: it is also interesting to think of the parallels not only as an influence, inspiration, quote or coincidence but as the unexpected meeting point between two artists separated by nine hundred years of history, united perhaps by geography and roots. Referring to a certain artistic trend that appeared in the West mainly from the 19th century onwards, primitivism, Vassily Kandinsky, in the introduction to his theoretical book On the Spiritual in Art (1917), pointed out that “the equality of the internal feeling of an entire period can logically lead to the use of forms that in a previous period positively served the same aspirations. Thus was born part of our sympathy, our understanding and our spiritual kinship with the primitives. Like us, those pure artists sought to reflect in their works only what was essential: the renunciation of the contingent appeared by itself”. It helps us understand the relationship, sometimes distorted, between ancient and contemporary.

Personatge i ocell, Joan Miró (1968). © Fundació Joan Miró

Personatge i ocell, Joan Miró (1968). © Fundació Joan Miró

What this crippled Vitruvian man expresses —since he proudly does not comply with any geometric canon within his circumference— he does so with his face: his open mouth cries out a message perhaps too distant, perhaps so close that it is chilling, like Edvard Munch's famous Scream. We could well adopt it as our own particular Angelus Novuus, because it resembles the painting by Paul Klee that inspired Walter Benjamin to talk about the ruins that history leaves behind, but Pedret's seems less catastrophic. Is it the expression of pathos or the "holy innocence" that plays a trick on us? In any case, the meeting between the two was real and the exhibition at the Museu Diocesà de Solsona, made without presumptuousness, can become, more than a grand theory, the confirmation of a sympathy and friendship between two artists as close as Cercs and Barcelona; as close as the first and second millennium after Christ.