Exhibitions

The twenties: between tradition and modernity

A selection of works by great European and Catalan artists that explain the decade at the Marc Domènech Gallery.

European art in the 1920s experienced a period of very interesting changes, marked by an intense dialogue between theory and practice. Not only were works created, but many artists also dedicated themselves to thinking and writing about what the art of the moment meant and should be. In Paris, for example, in 1920 the magazine L'Esprit Nouveau appeared, which brought together figures such as Paul Dermée , Le Corbusier , Pierre Jeanneret and Amédée Ozenfant , who defined the bases of purism, a movement that defended that geometry was present in all aspects of life, not only in paintings or sculptures. This implied valuing not only artistic form, but also industrial design, architecture and even typography, highlighting the importance of a formal order that transcended art.

This decade was also marked by the fact that many creators, after exploring the avant-garde, decided to look back and recover the figurative language and classical themes, such as motherhood or the Mediterranean Arcadia, an idealized space full of harmony. This movement, which can be traced roughly between the First and Second World Wars, is known as the “return to order.” Although at some point it was interpreted as a renunciation of progress or as a nostalgic gesture in difficult times, this look back can also be seen as a way to deal with the social upheaval and accelerated industrialization that had impacted Europe. Classicism, in this context, offered a certain refuge and a way to reinvent modernity, attempting to unite tradition and renewal in the same artistic space.

Femme assise, Manolo Hugué (1923).

Femme assise, Manolo Hugué (1923).

In Catalonia, this influence was noticeable very early on, as early as the mid-1910s. For example, Picasso painted his famous Harlequin in 1917, a work that he ended up giving to the Barcelona Museum of Art in 1921, a clear example of this tendency to review figuration from a renewed perspective.

The exhibition presented by the Marc Domènech Gallery until June 20 brings together some 25 works created between 1918 and 1930, with the presence of artists from all over Europe and here, such as Mariano Andreu , María Blanchard , Francisco Bores , Pere Créixams , Rafael Durancamps , Julio González , Manolo Hugué , Max Jacob , Le Corbusier , Jacques Lipchitz , André Masson , Joan Miró , Amédée Ozenfant , Pere Pruna , Josep Togores and Torres-García .

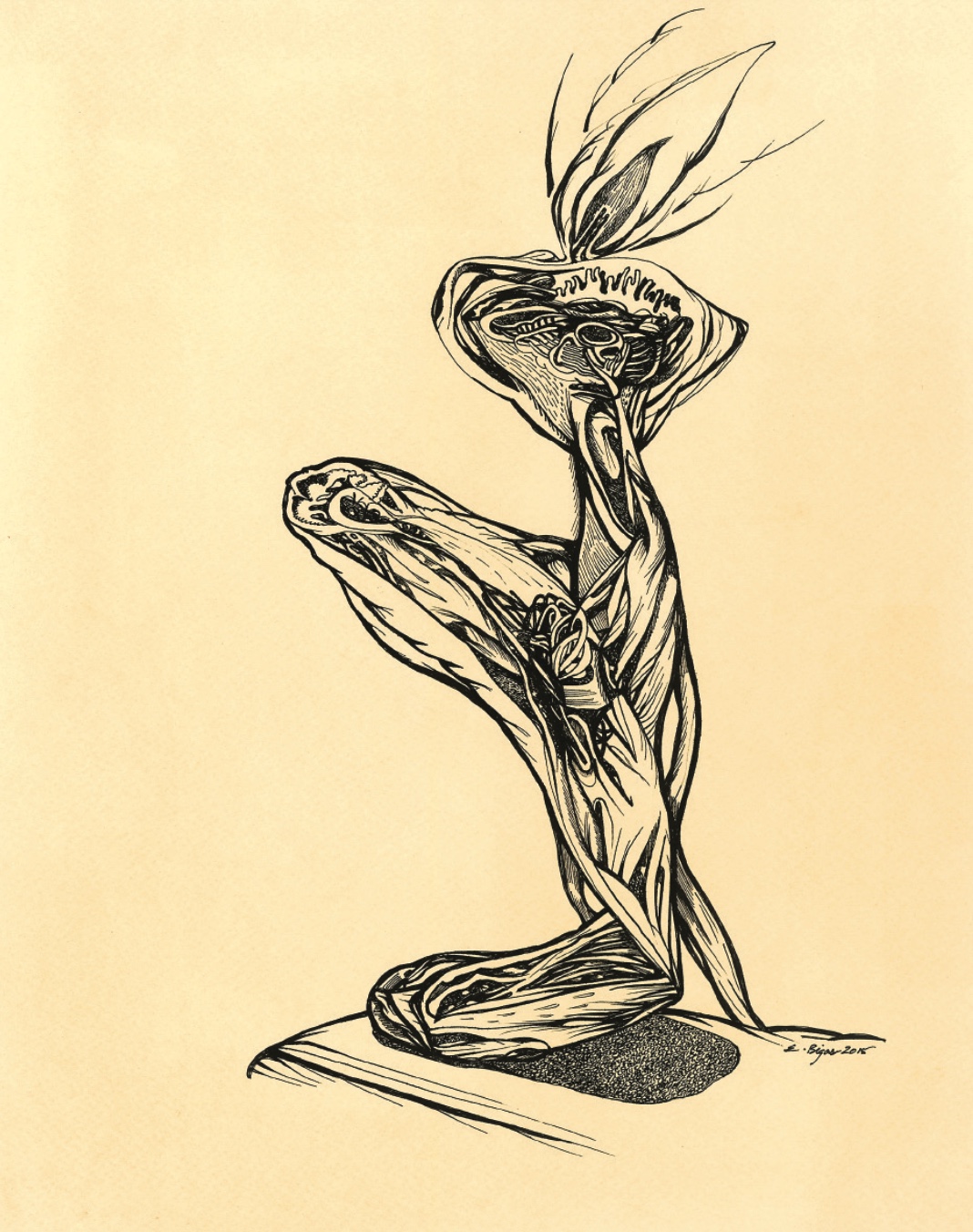

Among the pieces on display, the gallery highlights a drawing by Jacques Lipchitz from 1918 that, despite its cubist style, is clear and easy to follow. This work well reflects the search for balance and formal order that artists pursued to achieve this updated classicism. Also noteworthy is Les Sages Sensuelles by Mariano Andreu , a 1923 painting that captures the idyllic ideal of Mediterranean Arcadia. When it was presented at the Saló de Tardor, it was very well received, and Eugeni d'Ors praised it as one of the best examples of the new painting that mixed classical and modern references.

Les Sages sensuelles, Mariano Andreu (1923)

Les Sages sensuelles, Mariano Andreu (1923)

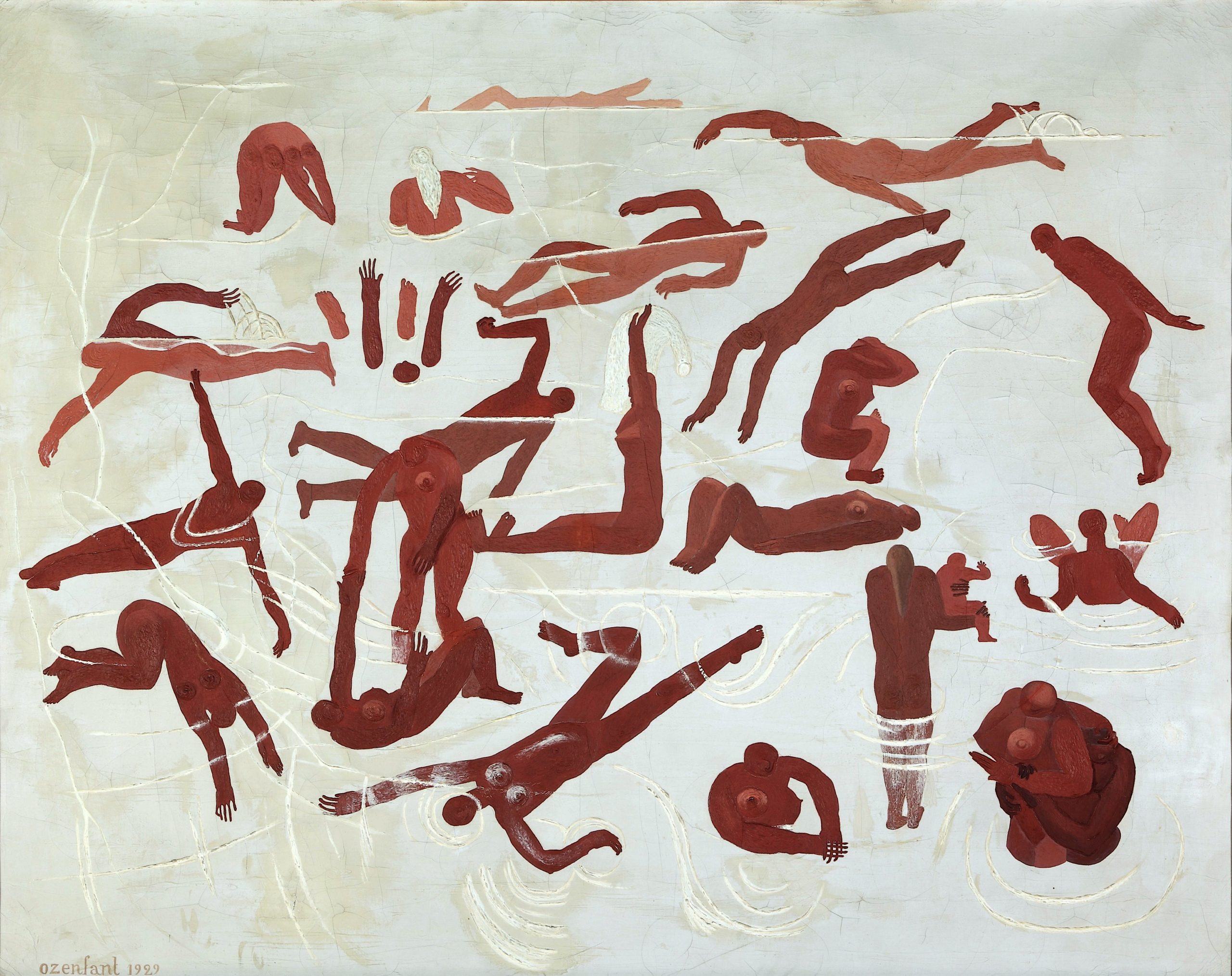

Another strong point of the exhibition is the presence of two works that represent the collaboration and theoretical approaches of Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant . Nature morte puriste (1923) and La belle vie (1929) are clear examples of the will to bring order and geometry to art. In this painting by Le Corbusier you can see how each form fits perfectly with the rest, while Ozenfant explores reliefs and earthy colors to connect with a classicism more linked to the Hellenic tradition, perhaps seeking stability in a world that was beginning to suffer from the uncertainties of the crisis of 1929.

In short, the exhibition allows us to see how that period, often simplified as a simple “return to tradition,” was actually a moment in which modernity and history mixed to create new forms of expression, in a context marked by the need for order and balance after a period of great social and cultural changes.

La belle vie, Amédée Ozenfant (1929)

La belle vie, Amédée Ozenfant (1929)