reports

Inhabit the museum

On the occasion of International Museum Day, a critical reflection on the role of museums and the need to rethink their models and foundations.

“Where is art?” some fans and not a few experts ask themselves when faced with certain aesthetic manifestations. Their comments tend to oscillate between disdainful rejection and well-intentioned interest in approaching new epistemological proposals. Both approaches have often been shown to be irreconcilable. Those who defend tradition would, in principle, oppose those interested in what is new. The debate has its roots in the famous quarrels between ancients and moderns, characteristic of the 17th and 18th centuries, a period in which the inevitability of a “scientific”, universal and exclusive, knowledge was proclaimed from Europe. At that time, academies and then museums were conceived, whose mission was to preserve and disseminate this knowledge. They decided what was true and what was false, and discriminated art from what was not. It could transform and evolve, but its essence had to remain unalterable, identical to itself.

Dispute was favored, not otherness or questioning, because there was no outside. All otherness was subsumed in a previous order. The successive European avant-garde movements, such as Fauvism, Expressionism or Cubism, were inspired by masks, fetishes and fabrics from Africa, America or the Pacific. However, they ignored the relationships that linked the effigies with the rituals that gave them meaning. Many of these objects were trapped in the category of “art”, despite the fact that the term did not even exist in the languages of force of these peoples.

Denilson Baniwa, Kwema/ Amanhecer/Dawn, Biennal de São Paulo, 2023. Foto: Levi Fanan

Denilson Baniwa, Kwema/ Amanhecer/Dawn, Biennal de São Paulo, 2023. Foto: Levi Fanan

Over time and in accordance with the same dynamics of capitalism, which grows by generating and overcoming its own crises, art centers have been mutating, adapting to their environment. In this way, the museum of the 21st century would have little to do with the one of a hundred years ago and much less with the one of two hundred years ago. It would be enough to compare the authors who were shown there, the exhibition devices that were designed or the audiences they were addressed to at that time with the current frenetic activity to build more inclusive stories, more immersive installations or to sponsor access to these centers for those who do not have them. The presence of indigenous or racialized curators in international events is increasingly important. The Documenta in Kassel and the Venice and São Paulo biennials are directed by African or Afro-descendant curators. This could not be more positive. But have artistic institutions really changed? The Venice Biennale continues to be based on a structure of national pavilions, as it was when it was inaugurated on April 30, 1895. In the case of Documenta, a federal law veiledly requires its directors to maintain Zionist positions. In a similar vein, museums enthusiastically welcome work from indigenous communities, but their collections continue to be based on the principles of ownership and accumulation. Nothing could be further from the light step and the drive to share of these peoples.

Museums operate in a specific historical context. Ours is marked by a neoconservative wave that is spreading inexorably across the planet. Far-right leaders use tactics and strategies aimed at manipulating citizens. In the 20th century, parties and marches in public spaces were the privileged technique for mobilizing the masses; in the 21st century, television parodies and the dominance of the screen mark the roadmap. Politics becomes, in both cases, a spectacle. Their goal: fascinating subjugation. In this sense, contemporary fascisms invoke historical ones. Adolf Hitler was said to be a “talking affection”. Fascisms are ontologically paranoid. They present themselves as victims of those they attack. This is what the ultra-media defines as “cultural Marxism”, which encompasses those who defend minorities, question and combat racism, heteropatriarchy, colonialism and extractivism. These are attributed to the supposed decadence of the West: insecurity, inequality, lack of freedoms, bureaucratization, etc. The so-called “fear of replacement” is exacerbated, the absurd idea that Western civilization is at risk of extinction due to foreigners. All this with one purpose: to cover up that the cause of these evils is, in reality, an oligopolistic regime that fascism protects.

Marcel Broodthaers, Una retrospectiva, Museu Nacional Centre d’Art Reina Sofia, 2016. Foto: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores

Marcel Broodthaers, Una retrospectiva, Museu Nacional Centre d’Art Reina Sofia, 2016. Foto: Joaquín Cortés/Román Lores

Marcel Broodthaers already argued in the 1970s that culture is a battlefield, which always takes place in enemy territory. The far right knows this well and does not stop in its push to impose the framework of discussion, because what is fundamental is not that what is asserted is true or false, but rather to define the guidelines and the context in which it is debated. Hence the need to take into account the place where the statements are made and the urgency of questioning our reference parameters. Otherwise, we run the risk of saying one thing and doing another, as when museums claim a friendly and listening culture and their managers continue to cling to individualistic and competitive criteria. Publications and exhibitions in art centers abound in vocabularies such as decolonization, restitution, redistribution, right to refusal, performativity, etc. However, these same centres, regardless of the good faith of their managers, have great difficulty in decolonising their structures and generating alternative forms of organisation. It is true that the boards of trustees are governed by a strict code of ethics and that xenophobic, racist or transphobic behaviour is less tolerated. Despite this, decision-making and procedures are, in essence, quite similar to those of a century ago. Perhaps a symptom of this is that European museums tend to have better relations with those populations living in their territories of origin than with the migrant communities located in their immediate surroundings, to whom they are frequently called upon to implement public programmes, generating experiences that are sometimes frustrating for these communities.

Sala dels monuments funeraris pagans, 1935. Arxiu fotogràfic del MAC.

Sala dels monuments funeraris pagans, 1935. Arxiu fotogràfic del MAC.

For most museums, inclusion and accessibility are their most relevant challenges. The intention is laudable. It is thought that it is enough to eliminate barriers and for people to know the history of art or the achievements of humanity so that this society, which the institutions serve, can improve. However, if the order in which these proposals are inscribed is not questioned from other epistemologies, the acquired erudition only increases the weight of the past or ideas on our shoulders, reaffirming the status quo and preventing any possibility of rupture. Western cultural entities assume that, for an artist or a peripheral community, what is substantial is to be there. Different options are not taken into account. Those excluded from the unique story can be “appreciated” with a little effort, on their part or on the part of the entities that welcome them. Perhaps these authors did not enjoy —it is believed— the necessary opportunities. Or, at the time, experts were not able to grasp the good and beautiful in artistic manifestations that exceeded the norm. But, sometimes, this recognition only occurs from absorption or identification with the “accepted” culture. The ubiquitous phrase that appeared on the posters of the 60th Venice Biennale (2024), “this is the first time this artist has exhibited at the Biennale”, and its insertion into a colonial exhibition device clearly indicated this. It is not a question of entering the system, but of leaving it. More than “arriving” at the museum, it would be necessary to promote its exodus, the escape from (self-)imposed limits. Decolonizing does not mean merely restoring. It means making amends and healing. Reparation cannot come from those who caused the damage. It is the peoples who have suffered dispossession who will decide what to do and how to do it. It is not enough to reform the museum. The essential thing is to imagine, from its ruins, other stories, devices and forms of organization.

Piràmide de vidre d’Ieoh Ming Pei al Louvre. © Mitchell Rocheleau

Piràmide de vidre d’Ieoh Ming Pei al Louvre. © Mitchell Rocheleau

Some time ago, the Italian critic Marco Baravalle proposed inhabiting the museum, instead of visiting it. The verb “inhabit” comes from the Latin habitare, which means “to have repeatedly”, to make something or a territory your own. This is different from some anecdotal and literal approaches, frequent in certain areas of contemporary art, which consist of organizing a meal or a leisure event. One could say that inhabiting is the way of being and being in the world. Inhabiting a museum implies that society makes it its own. Understanding it as a zone of institutional experimentation, that is, as a space in which our greatest desires and our worst fears are negotiated; and in which, in doing so, other universes can be invented. The inhabited museum is not ordered by themes, genres or styles. It is articulated based on relationships. Instead of delimiting and representing the milestones of national history, the inhabited museum moves in the borderland, because that is where, following Gloria Anzaldúa, the reconstruction of the collective identities of the diaspora or those located beyond coloniality takes place. For this reason, it is essential to reduce the scale and weave a warp of micro-narratives with the aim of distinguishing that the territory in conflict, by the simple fact of being shared, hosts more stories than those that make up the national story. These stories feed on what each one denies about the other, and between the mutual denial, the space is created in which the rumor of the narrative of the expelled population, which has been suppressed and which is established against the grain of the others, is configured. “Will I be able to belong without belonging? Being a citizen, yes; but second-class. Perhaps, isn't this a non-belonging belonging, or better, a belonging, let's say, belonging? They continue to be two positions in tension that should be exclusive and, nevertheless, they are two positions whose overlap configures a social identity.”

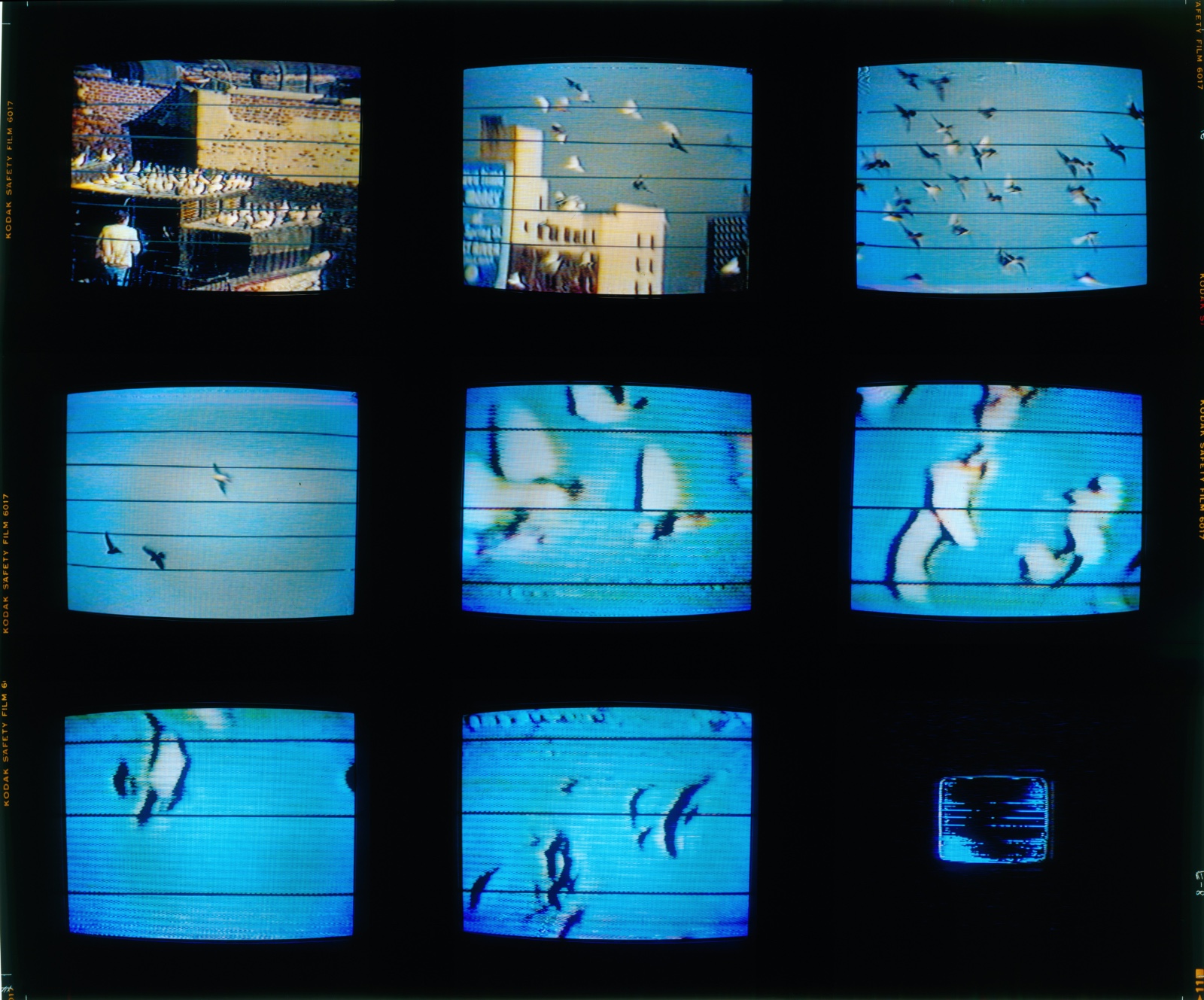

ugènia Balcells. From the center, Moons, 1982

ugènia Balcells. From the center, Moons, 1982

Accustomed as we are to the fact that only those who inhabit a territory enjoy their own narrative, we have not been able to construct a history in which narratives have more to do with relationships than with identities. Unlike the latter, the former are not fixed. Beyond reductive classifications such as “Catalan art”, “Spanish”, “Latin American” or even more recent concepts such as “Afro-American”, we should talk about the flows and encounters that occurred on both sides of the Atlantic. On the other hand, while Foucault understood the immobilization of people in prison as a form of control, this is exercised today based on mobility. The diaspora has become a state of permanent deportation, which is the condition of many people without a voice in history. Forced migrations, planned displacements, exiles are part of our condition. The silences of history are marked by them.

In his introduction to the book by Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, Jack Halberstam mentioned the famous story by Maurice Sendak: Where the Wild Things Are. For Halberstam, the protagonist of the story finds himself immersed in a journey to a world that is no longer the one he left, but which is also not the one to which, at first, he thought of returning. For him, this is the most important element of Harney and Moten's text. We cannot imagine a future when we start from a reality that is unjust, whose form of knowledge is imposed on us and does not let us see beyond its limits. It is impossible to end colonialism if we fight with its tools and truths. It is inevitable that we will find ourselves in a space that has been abandoned by what is regulated and normative. It is an indomitable, frontier space that exists beyond colonial reason, it is not an idyllic utopia, it exists in many situations: in jazz, in the improvisation of performance, in noise, in the enigma of what is poetic. This “other place” is already present in our desire. As Moten says: “The disordered sounds that we refer to as cacophony will always be considered extramusical precisely because we hear something in them that reminds us that our desire for harmony is arbitrary and, in another world, harmony would sound incomprehensible. Listening to cacophony and noise tells us that there is a wild beyond the structures that we inhabit and that inhabit us.”

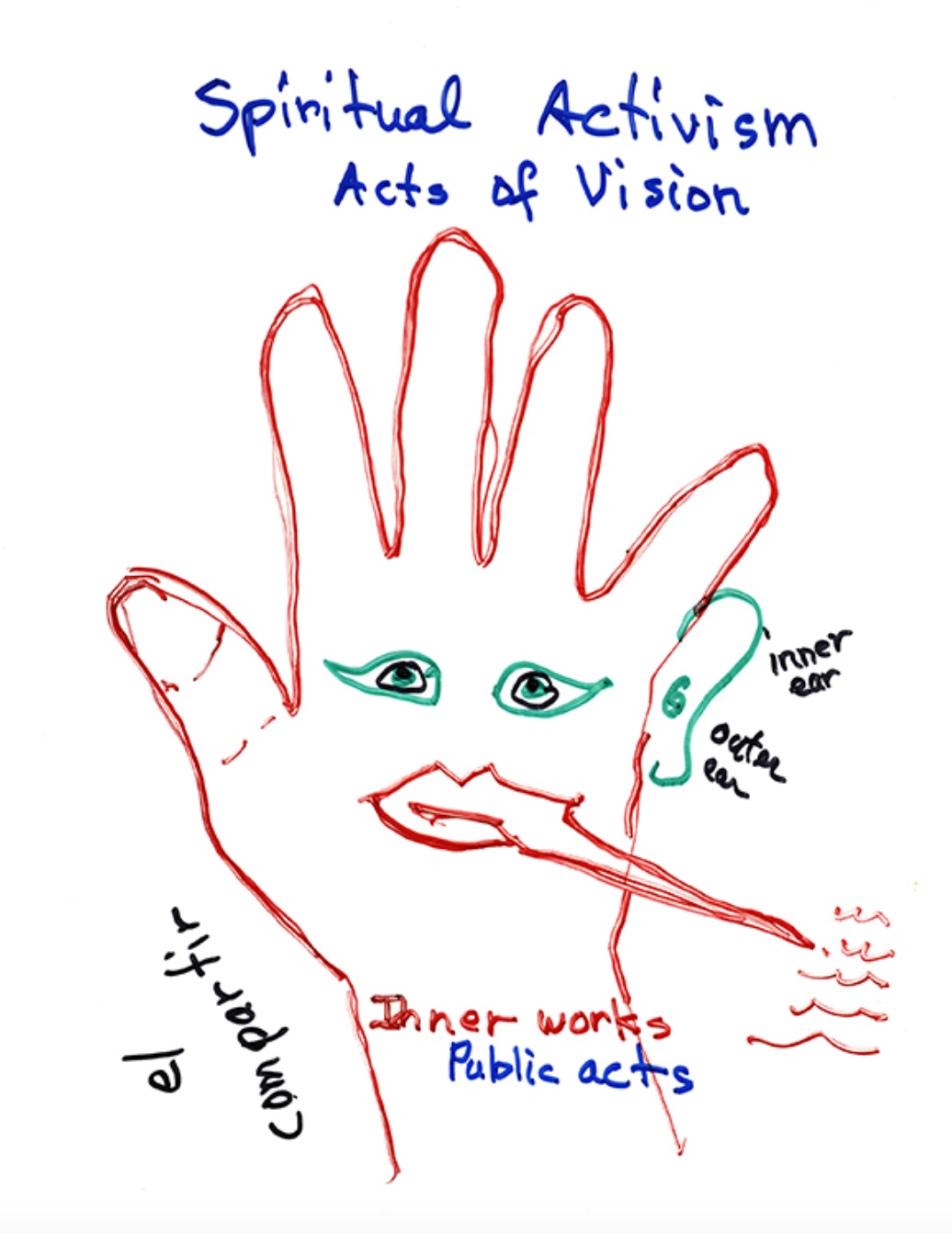

Gloria Anzaldúa, Spiritual Activism

Gloria Anzaldúa, Spiritual Activism

“Where is art?” our interlocutors ask themselves. The answer would be: “Everywhere.” This does not mean dissolving art in an aestheticized vision of ordinary life and politics, fostered by consumerism and the new fascisms, in which everyone is an artist or a happy consumer. This “art” would reside in its own exteriority, in that of those who participate critically in the construction of a shared history. Each from a specific position and ways of doing things, in an institution to come.