Exhibitions

Stick your head inside.

The Espai Isern Dalmau in Barcelona in collaboration with the Miguel Marcos Gallery presents the exhibition [NO] Taking Your Head Inside by Bernardí Roig. The show consists of four videos and an installation called Goya's Head (2020). At the entrance, the sculpture of a contemporary Sisyphus seems destined to drag a bundle of colored neon lights with the resignation of guilt. Bernardí Roig challenges us by throwing ourselves into a light that if we do not know how to see it, we will carry it on us like a heavy sack, as happens to the figure that welcomes us at the entrance to this exhibition.

Then, faces and heads guide us along the journey carefully thought out by the artist and we come across the work "The Shipwreck of the Face" (2015), a self-portrait that looks at us and that slowly evolves in appearance over 365 days. In the background, his father's face, drawn without touching the paper, leaves the iconic imprint of a light face, evanescent like that of a shroud.

Further into the room, behind the first faces, more heads appear. On the left, “Repulsion exercises” (Salomé), 2006, here there is no silver tray with the prophet's head. Nor a mother to whom to bring his decapitated head. We see a bronze head that rolls around, pushed by the kicks of a woman in high heels, who scolds him and urinates on him.

Urination is also the focus of the following video “Watch your head” (Actaeon's Bath) an inverted version of the Greek myth of the golden rain referring to the story of Diana. We see a male sculpture locked under a grate in the middle of the asphalt of a large city. The urban centaur is locked up as Diana was locked in a bronze cell by her father. A rain of gold, liberating, falls on his face. Just as Zeus did by transforming himself into a rain of gold to enter Diana's cell, fertilizing her.

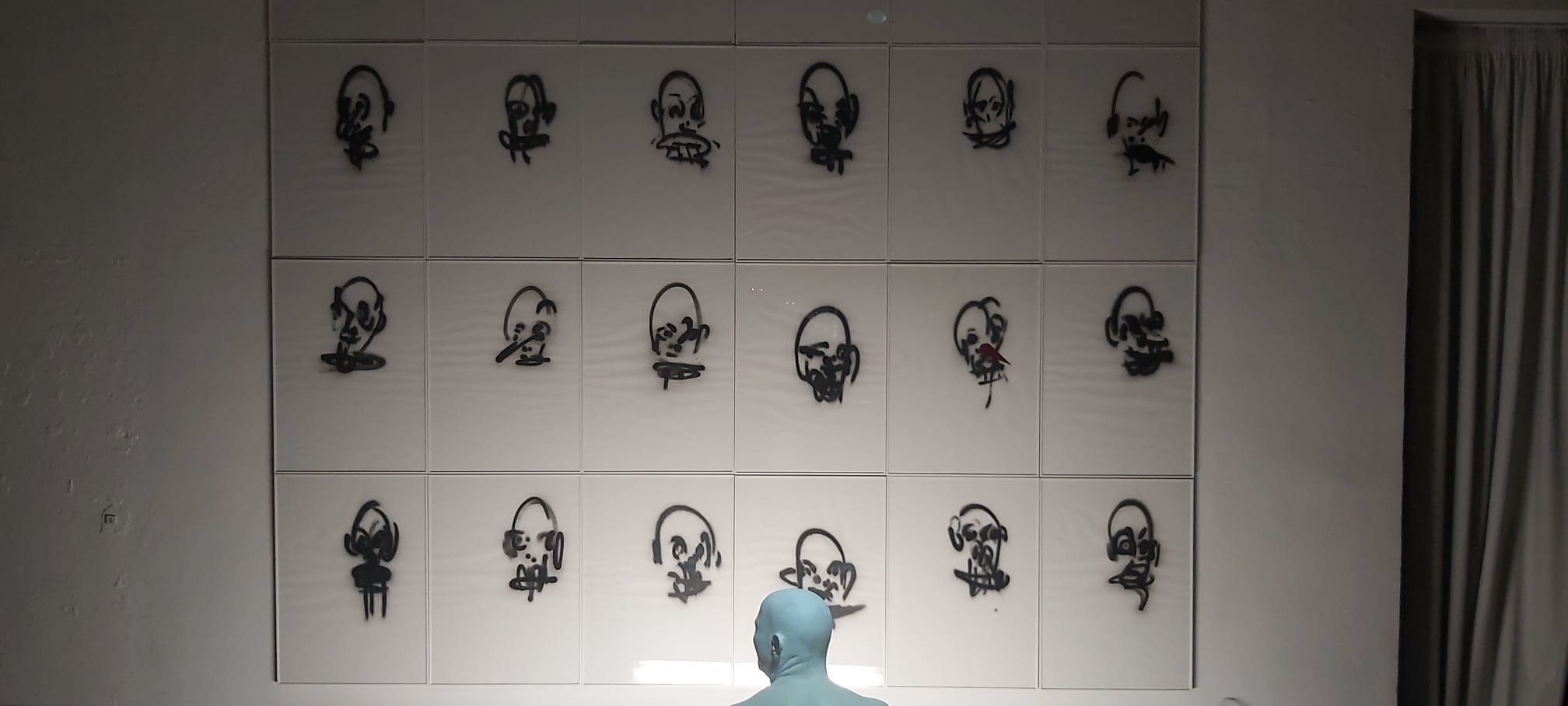

Between the two videos there is an installation that seems like a separate point “Goya's Head” (2020) which refers to a historical event. Goya dies in exile in Bordeaux, no one claims his body until sixty years later, when the tomb is opened and the remains of the body appear, but the head is not there. Perhaps a consequence of having cultivated the dark side of existence. About this beheading Bernardí Roig makes thirty drawings with the intention of imagining the possible portrait of the absent head, they are light drawings almost calligraphies, unlike the 3 kg that an adult head can weigh, by the way, the same weight as the statue of the film awards that bears his name.

A figure sitting in front of the drawings has wounded and golden eyes, perhaps the trace of some gold brooches and everything seems like a new mythical allegory, that of Oedipus, and the incest with Jocasta, his mother. I say seems, because in the context of the work on Goya's head I consider it more of a corroboration that the gaze is not always outward, but also inward.

This is demonstrated by the fact that in front of the installation, Bernardí Roig explains to us that this absence of the stolen and lost head, gives rise to each of us to do the exercise of reunion and contemplate his thought, the same mind, the same brain. It is an invitation to take out the NO, to eliminate the initial negation of leaving it as "Take your head inside", this encouraged me to make the following interpretative approach.

One way to get the head inside is through what we could call mystical acephaly. We have seen the severed head and its iconography with the Baptist as revenge, but it can also be a source of knowledge. We find this iconography in the West with Zurbarán's decapitated monk, who contemplates his own severed head, let's say he contemplates himself in an exercise of full awareness. Francesc Torres used this image for his installation "Losing His Head" at the Tecla Sala (April 2000), a glass figure of the monk's body painted to life-size, while the head turns and turns on an airport luggage conveyor belt. We also find something similar in the East with Chhinnamasta, a tantric Hindu goddess who beheads herself by cutting off the illusion of the ego, the self and the fog of thoughts, which do not or cannot connect directly with the true reality of the being itself.

Both cases indicate the necessary virtuous action that emerges from this inward look that the title of the exhibition proposes to us. It is an invitation to delve into our mind, it is a necessary self-awareness, but, even more, it is also a way of reminding ourselves that if we contemplate in stillness, inwardly our center of consciousness, our interior with a naked mind, which goes beyond conventional ways of thinking, we will penetrate the "darkness of not-knowing", in which all apprehension of routine understanding is renounced and where only listening, the contemplative silencing of who we are, is possible.

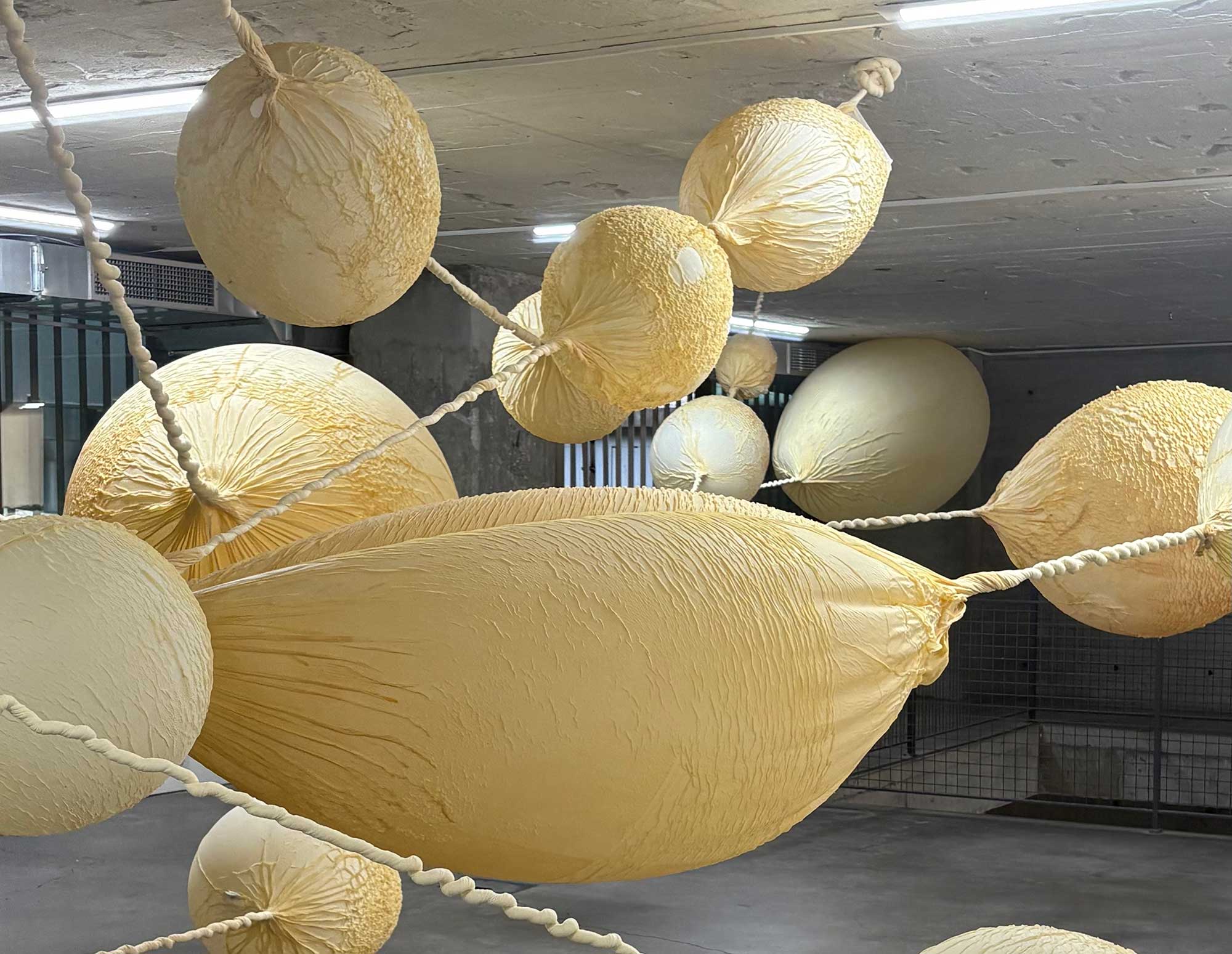

The tour ends with a click of the eye typical of the postmodern condition: “la joie de vivre” (2018), a double quotation, a tribute to the well-known painting by Matisse where we also find the sketch of his dance of women with generous bodies celebrating life, as we see them dancing in the “Tabacalera” of Madrid, the postmodern stage par excellence, now abandoned. Apparently, a “field trip” by the artist in the tour that we had marked out until now, but not so much, because perhaps, as Matisse intended, it is an invitation to let oneself be carried away, a song to existence as a result of this turning one's head inward.