Editorial

Glass cliffs: cultural rights as a democratic urgency

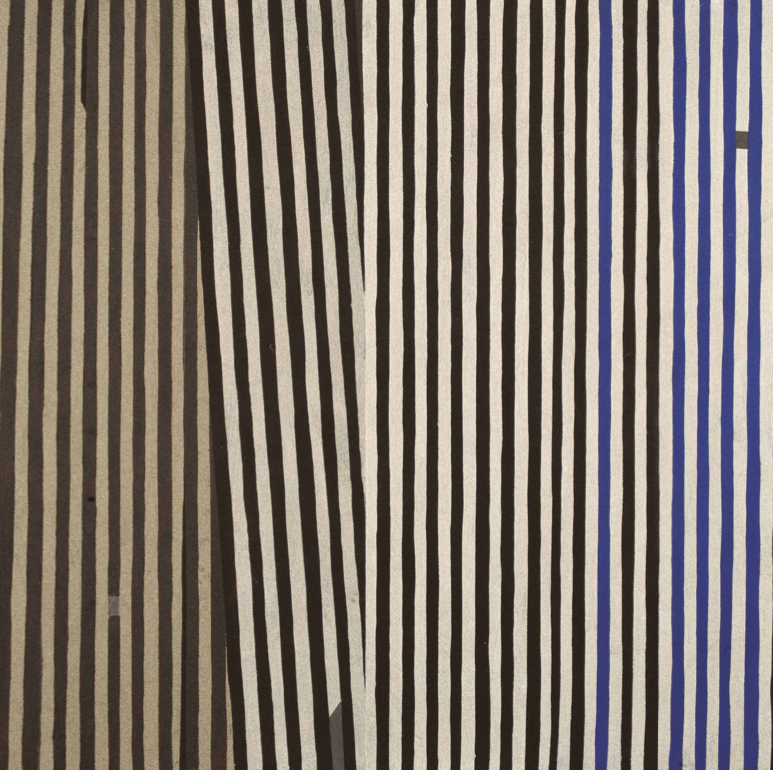

Culture is not a luxury, nor a premium weekend subscription. It is a right, an innate capacity, as Joseph Beuys defended: we are all artists because we are all beings capable of creating. Reducing culture to an object of consumption is amputating citizenship.

Talking about cultural rights implies talking about equity, equal access, real participation. It is not enough that museums or theaters exist: the question is who can enter, who is recognized there and who is left out.

Institutions cannot limit themselves to programming activities. Their responsibility is twofold: to guarantee the infrastructure so that no one is excluded and to provide culture with financial support, because without a budget there are no rights, only declarations. Investing in culture is not philanthropy: it is an investment in democracy.

At the Center for Contemporary Culture of Barcelona (CCCB), the panel on Cultural Rights and the New Global Challenges on September 9 that I was able to attend, within the framework of the Ibero-American meeting on Cultural Rights and the Creative Economy, brought together voices from Costa Rica, Peru, Spain, Panama and Brazil - I missed countries as prominent as Mexico and Colombia, which have not yet joined the Organization of Ibero-American States for Education, Science and Culture (OEI). It must be said that it is always interesting to look for the subtlety and connotations that it implies when speaking with the term Ibero-America or Latin America. But, let's return to the panel. Their contributions converged on a key idea: cultural rights must be the engine of social cohesion in Latin America and in the world. They talked about regulations, professional recognition, gender mainstreaming and culture as a vector for the 2030 Agenda and the next Mondiacult 2025. A Latin American mosaic that demonstrates that solutions are not local, but shared.

In Latin America, this reflection is not new: for years, several countries have created ministries or national departments specifically dedicated to cultural rights. Brazil, for example, has the Fundação Nacional das Artes (Funarte) and a Secretariat of Citizenship and Cultural Diversity that place rights at the center; Panama has created a National Directorate of Cultural Rights and Citizenship; and in Mexico, the Secretariat of Culture incorporates programs that recognize cultural rights as part of democratic life. These precedents show that the region has been able to move forward and offer inspiring models for the global debate.

And perhaps the concept that surprised me the most was that of "Glass Cliffs" (Acantilados de cristal) and that is when governments function, women are not usually in the front row; but when everything shakes, they enter to manage the risk. This paradox —the glass cliff— also crosses culture: why are they delegated only when the ground cracks? The challenge is to guarantee structural equality, not to turn fragility into destiny.

Cultural rights are the only way to sustain plural societies in a world in climate, digital and political crisis. It is not enough to proclaim that "culture unites us": it must be funded, opened up and redistributed. Because without culture there is no citizenship. And without citizenship there is no democracy.