Opinion

Claiming Tàpies' 'The Sock'

In the early 1990s, Antoni Tàpies carried out a monumental project for the large oval hall of the Palau Nacional de Montjuïc, when I myself was directing the MNAC and the architect Gae Aulenti was working on the building and the museum. It was an 18-metre-high sculpture representing a sock with a hole in it with its heel raised, which was to hang from the ceiling, accompanied and supported by a series of cross-shaped pieces. The whole was made of metal mesh and fibreglass with an internal structure of metal tubes. Tàpies had conceived this monument as a space of intimacy, where one could enter to reflect.

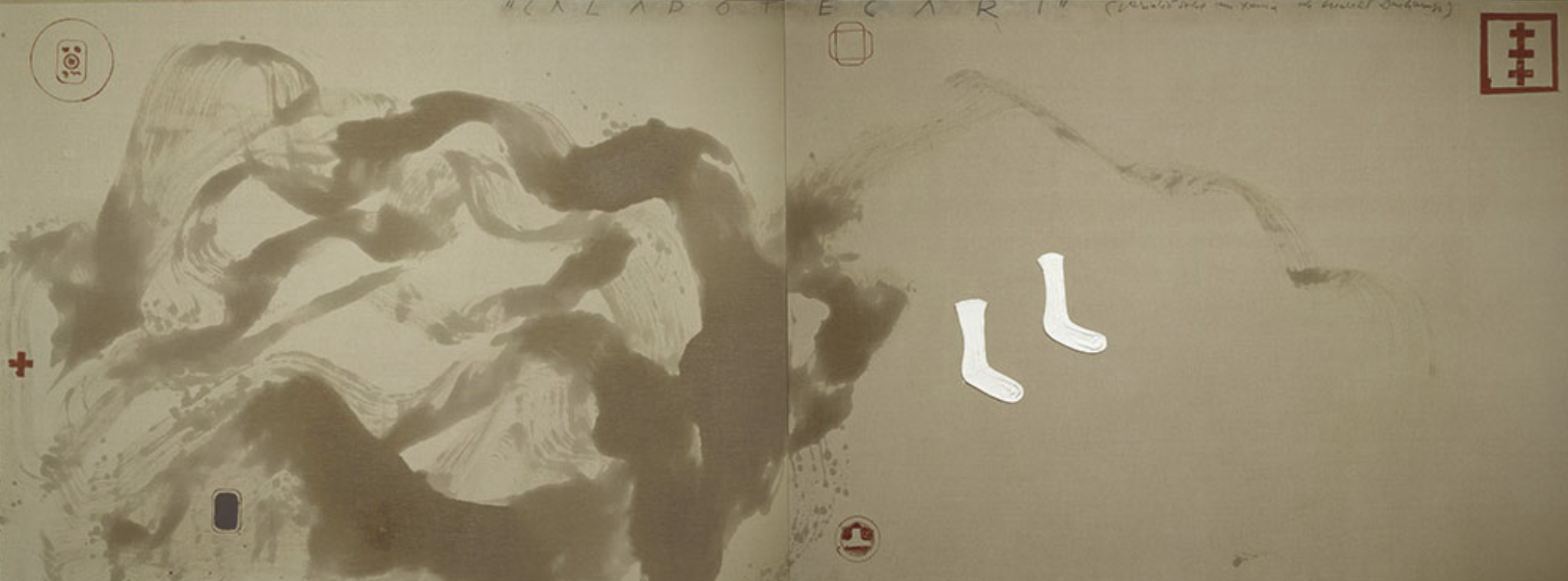

The project sparked strong public controversy at the time between defenders and detractors. It was eventually discarded. Tàpies suffered greatly from this rejection. I defended the realization until the last moment, convinced that this work would bring many people to the museum, an audience that would come to visit the works of the past but also to admire a major Tapiesan achievement. It was, for me, an incentive, an additional advertisement for the museum. In this work, Tàpies had brought together usual elements of his artistic language. Let us remember, for example, the Great Diptych of Socks, from 1987, today in the Fundació Antoni Tàpies.

Gran dípctic dels mitjons, Antoni Tàpies (1987)

Gran dípctic dels mitjons, Antoni Tàpies (1987)

Socks, very frequent in Tàpies' works, were for him symbols of everyday life, and if he also represented them with holes and worn out, it was to dignify the humblest object. Taking it to the dimension of a secular chapel, a space for personal reflection, the artist proposed for the MNAC a work of absolute posterity that also corresponded to his concept of a museum when he said, ten years later, in an interview with Arnau Puig in March 2002: "Museums have become a popular spectacle, abandoning the path of spirit and sacredness that, ultimately, is art." Today, the memory of that great controversy and the generous proposal that the artist made for his city and for the most important museum in the country has almost been lost. With this work, Tàpies would have become even more immortal and the museum would have had a realization with great power of attraction. Although a reduced-format reproduction has been made at the Tàpies Foundation in Barcelona, it seemed to me that in the years of the celebrations of the centenary of Antoni Tàpies' birth, it was necessary to claim this work and, why not, to demand that it one day be installed in the place for which it had been conceived.