Exhibitions

Mar Arza: it is not by chance that the patriarchy falls

The persistence of patriarchal structures through language, technique and space.

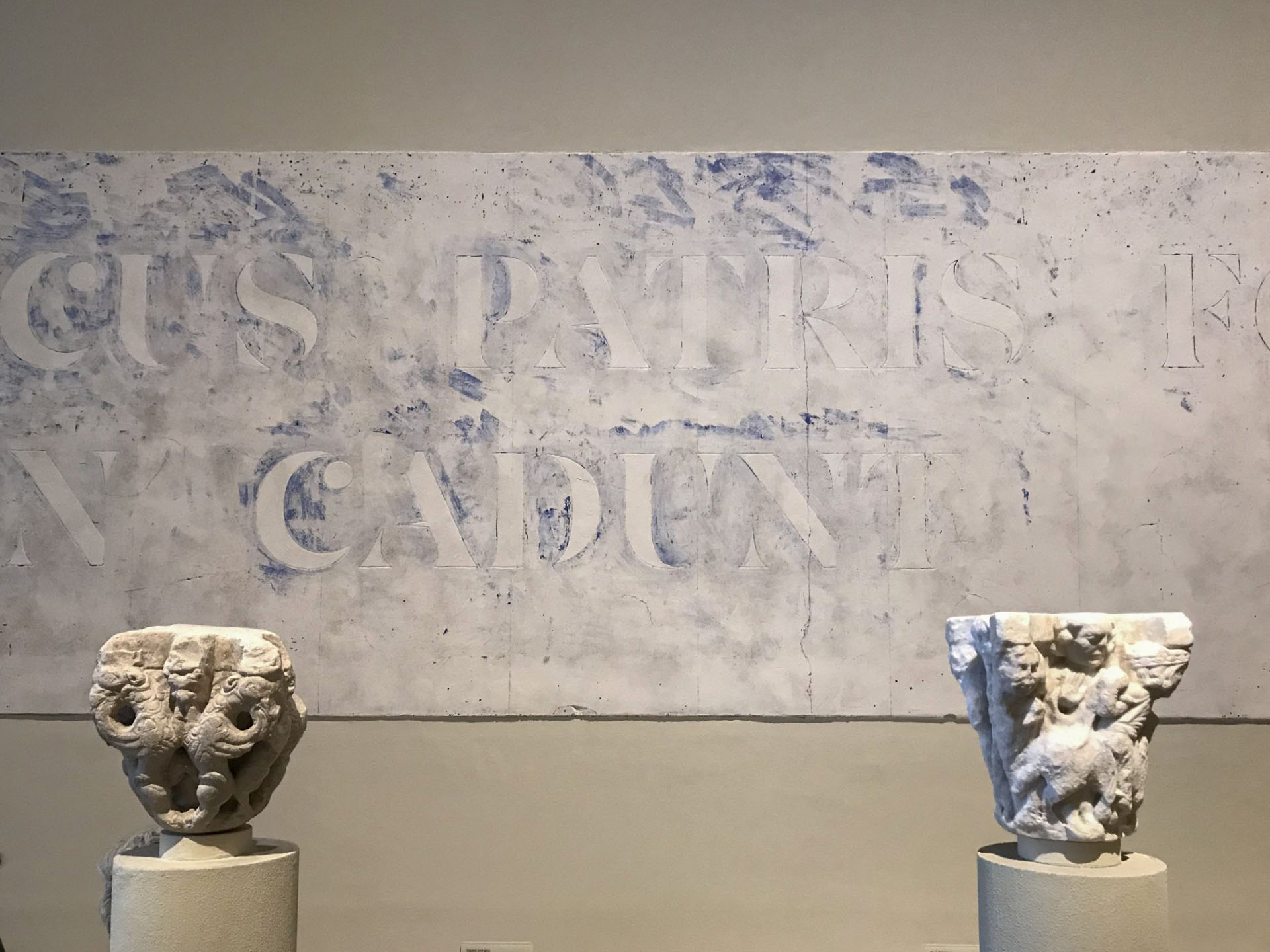

One of the walls of the Romanesque rooms at the MNAC now shows the remains of a torn painting. However, it is not a fragment rescued from the Pyrenees like the rest of the frescoes that surround it, but a contemporary intervention by Mar Arza (Castelló de la Plana, 1976) that enters into dialogue with these thousand-year-old paintings to raise a still-current question: how are the structures that sustain power maintained, and why are they so difficult to bring down.

The project, entitled Strappo. It is not by chance that the patriarchy falls, is based on the technique that allowed many of the Romanesque paintings that we can see there today to be transferred to the museum. Strappo consists of gluing a very thin cloth to the surface of a fresco; when it is torn off, the top layer of paint is removed, which can then be fixed on a new support. What remains on the original wall is a kind of visual echo, an imprint that keeps track of what was there.

Fragment de vestigi d’un ésser del bestiari de Sant Joan de Boí. MNAC

Fragment de vestigi d’un ésser del bestiari de Sant Joan de Boí. MNAC

From this image – that of the painting that is not completely erased and that continues to be present as a mark – Mar Arza constructs a metaphor about the persistence of patriarchal structures. "The reflection on the patriarchy that is present and that is often made invisible merged with the fascination for this fresco painting that never quite leaves its place, but is so much of the place that it is impregnated on the wall", explains the artist. His fresco, created expressly for one of the walls between the paintings of Sant Climent and Santa Maria de Taüll, included a phrase written in Latin: ARCUS PATRIS FORTE NON CADUNT.

This inscription, translated, means: "The father's arches do not fall by chance." Mar Arza wanted to work with the Latin language to integrate into the space, but he faced a challenge: how to talk about patriarchy in a language in which this concept, as a word, did not yet exist? It would have been an anachronism. With the help of Mercè Otero, professor of Latin, they reflected together on how to formulate this idea. At the same time, the relationship with the capitals and columns gained weight, until a poetic turn occurred: patriarchy, etymologically, is the government of the father —patris, "father", and arche, from the Greek, "government".

The intervention involved both the creation of the fresco and its subsequent extraction. This process, carried out with the help of a specialized technical team, included the preparation of the wall, the application of the fresco at the ideal moment of humidity and, once dry, the removal using cotton fabrics and organic glue. The result is a work that is not seen in its entirety, but is suggested through what is left on the wall. Fragments of paint, layers that could not be completely extracted, and a presence that continues to permeate the space.

With this action, Mar Arza continues a line of work where language acquires a physical and sculptural presence. She had already explored this in other pieces with watermarked papers, where the word “patriarchy” appeared as a subtle but persistent imprint. Now, on this wall of the MNAC, the imprint is more than a metaphor, it is a layer that resists being completely erased, a structure that is not seen, but is there.