library

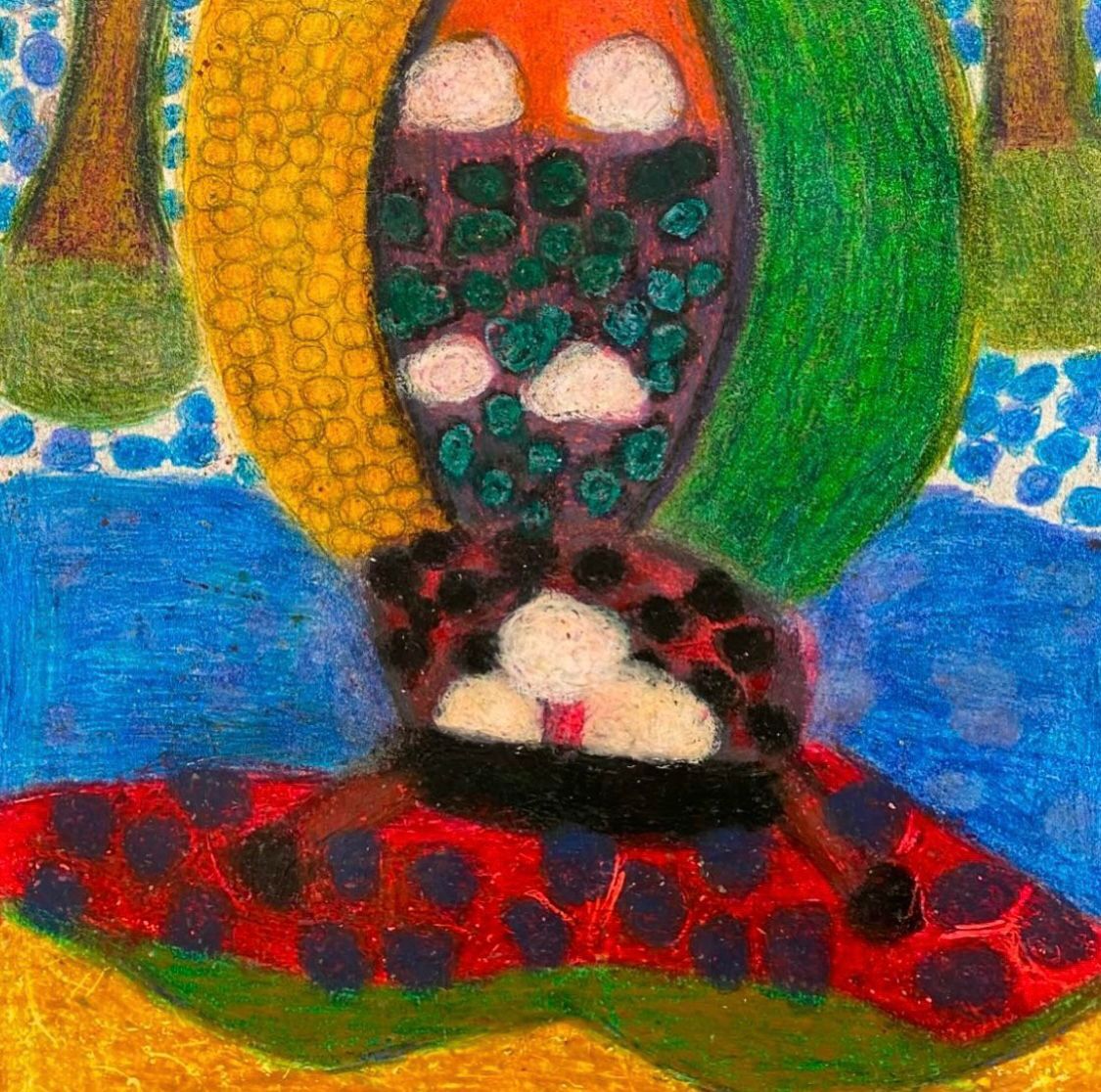

Without labels and against the empire of normality

The recent publication of the catalogue of the Singular Guissona Collection is the product of the collaboration between the Josep Santacreu Foundation and the BonÀrea Foundation. The volume brings together the works of 23 authors and authors who work from a neurodivergent condition. The works arise in the workshops of entities such as the Catalan Foundation for Cerebral Palsy, the Estimia Foundation, the Asproseat Foundation, Cal Santacreu and the Day Care Services of the Ampans Foundation.

An increasingly important reality, with a significant weight in the lives of all those who participate. Users, entities and families form a network that allows a space for creation without necessarily being considered a clinical space, but simply therapeutic. However, as Eva Calatayud, director of the ArtSingular program at the Josep Santacreu Foundation and author of this compilation, says, this is a work without institutional registration in the network of public and even private museums. While the art system has assumed to become the reflection of a world that incorporates new rights every day, in an arc that goes from decoloniality to the queer spectrum, the limit of this apparent openness is marked by neurodivergence. Production carried out in psychiatric environments has traditionally been labeled as a marginal modality. But, when it has been recognized, it has been done from the parameters of a neurotypical art history.

The emergence of art brut during the post-war years in Europe has profoundly marked our relationship with the expressions derived from neurodivergent people. The term art brut fills a hole of unknown dimensions in the way we understand 20th century art. The artist Jean Dubuffet coined it from a company dedicated to systematically extracting the creations made by patients admitted to psychiatric institutions and then bringing them into the art world.

An extraction inspired by the ethnographic enterprises that, in the late 1920s and 1930s, gave rise to the birth of collections and museums with the ambition of having a universal reach. Among other reasons, because the objective was as ambitious as representing the evolution of humanity. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, issued in Paris in 1948, came to close a traumatic period in which the end of the world was experienced as a transversal delirium that would affect people with a declared pathology as much as those supposedly normal. After the war, that suffering had been the laboratory for conceiving a new humanism. Art Brut aspired, nothing more and nothing less, to integrate madness into this new era of humanity that was emerging badly wounded from the war conflict. That model of integration prioritized an institutional segregation that, with the excuse of protecting a radical difference, kept the creations of psychiatric people on the margins of the rest of the art system.

Now the challenge is clear: incorporating the creations of authors such as those included in this volume edited by ArtSingular implies a questioning of the “empire of normality”, as translated in art institutions. For this reason, effective recognition cannot be achieved by isolating the works for the umpteenth time. They must be presented and disseminated as objects integrated into a therapeutic device. The volume we are talking about accompanies the introduction of each author – which, by the way, does not provide any label or clinical diagnosis of the users – with the testimony of the monitors. One of them, Petra Gaule, summarizes the atmosphere of these workshops and says: “Everyone works with great concentration and enthusiasm. They show all their creativity. There are no breaks, they make the most of their time, they don't waste a minute, and this can be seen in the results.”

Results that, however, do not circulate under conditions of equality in our public space. The labels often added to indicate where these types of works come from remind us that we do not share the same conditions of citizenship and that there are significant differences. Works such as those included in this catalogue denounce an imbalance of the parties and, at the same time, propose a meeting point between those who created them and those who consider them works of aesthetic interest. The quality of this meeting point is what really matters, what should move us.