Editorial

Everything is good, what the pot cooks

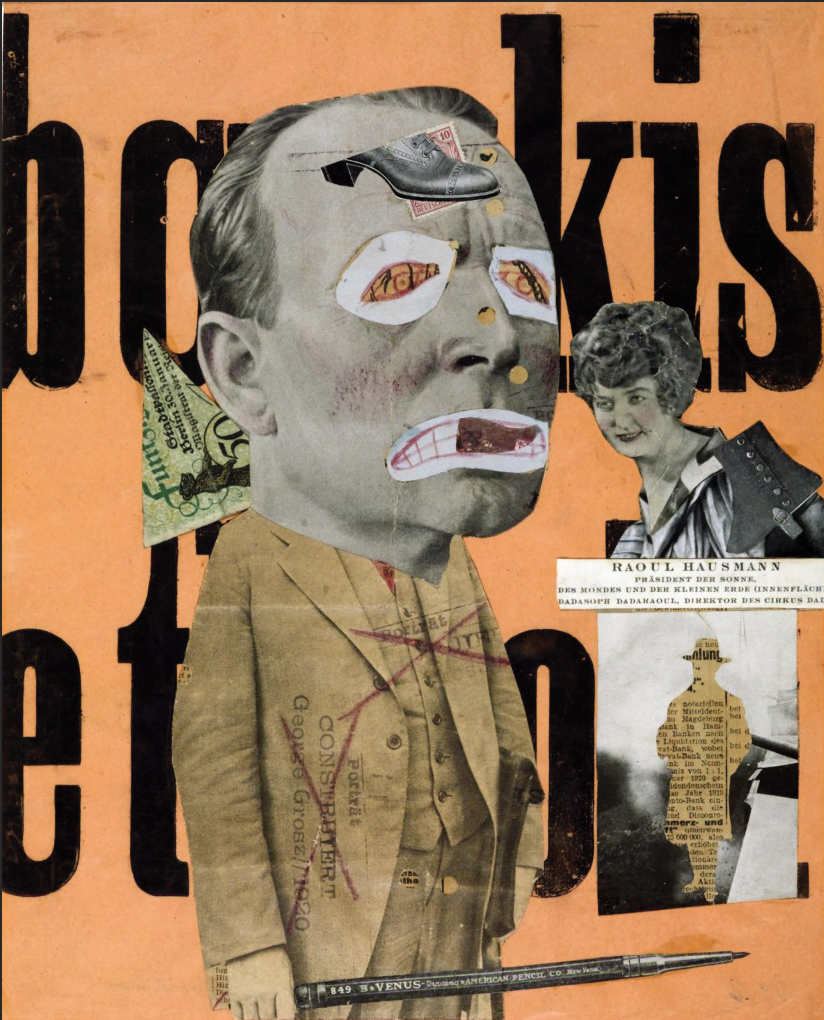

The serial attack on a whole series of works of art by activists against climate change has been the topic of conversation on which we have all played to position ourselves. Sometimes this positioning touches on sensibilities that are more practical than aesthetic, and one ends up thinking about the labor consequences of the person in charge of watching over that room or the extra work that the restoration team will have to fit in between the work already scheduled. Thus, the environmental cause and the artistic value are, equally, not relegated but rather as another conditioning factor of the fact.

The truth is that museums have undoubtedly become victims of these acts of vandalism which, without a doubt, have a greater impact on the daily work of the museum community than on environmental awareness. Every action supposes the activation of connections that involve other aspects of a more empathic nature, even ridiculously anecdotal. I remembered sibling fights and how the best revenge was destroying the thing you knew your brother cherished the most, the thing you were strictly forbidden to touch, look at, or even breathe within 10 inches of. That which had the luster of revenge.

There have been many revenges in art. In 1914 the suffragette Mary Richardson attacked Velázquez's Venus in the Mirror to demand women's suffrage in the United Kingdom. But it is only one example of the many acts of iconoclasm that have nourished the histories of art. The most well-known, the iconoclastic quarrel that took place in the Byzantine Empire in the 8th-10th centuries, is used in many arguments as a prominent event of this destruction of images. The truth is that on that occasion, as on so many others, the discussion was not properly directed against art but against religious representations. The image was not so much what was presented as what it represented, and that was none other than the political and religious motives that pitted the emperors against the increasing power of the monasticism. In the first third of the 20th century, the School of Annals helped us to understand a little more the meaning of history and made it clear that historical interest did not lie in the political event or in the individual itself, but in the processes and social structures that surrounded them. Thus, what is social also has an impact on artistic production so that, as Bruno Latour points out, the object/thing produces a specific sociability at the same time as it produces a space. For this reason, far from tearing our clothes, peace of mind, works of art are and will be everything they produce and destroy beyond their golden showcase.

On the other hand, these actions and the consequent reactions highlight the character of precious showcase that we have cultivated around the world of art. We emphasize that many of the attacks have occurred in European museums. You don't respect what you don't feel as your own. Perhaps, and beyond the relevance of environmental protest, excessive preciousness has led us to see artistic objects as targets to attack and not as what they are supposed to represent, i.e. cultural values shared that build us and that revert to the growth of the community in which we live.