Exhibitions

Miralda, BOOOM

A visual and critical journey through military iconography and its deconstruction.

The Senda gallery is hosting a new exhibition dedicated to Antoni Miralda (Terrassa, 1942), an artist who since the sixties has built a very personal career between political criticism, humor and action. This time, the focus falls on a very specific part of his work, the one that revolves around the soldier, military structures and everything they represent. It is a look towards the past with a power that, despite the years, resonates strongly in the present.

The reason for the exhibition is the presentation of the book BOOOM 1962-1972, edited by Ignasi Duarte and co-edited by La Fábrica, which covers a key decade in Miralda's work. In the gallery, the book takes shape through a selection of photographs, drawings and sculptures, many of which have never been seen before. The exhibition puts on the table the way in which Miralda began to document —and at the same time transform— his experience as a recruit during his military service. It all starts in Los Castillejos, in 1962, when the camera becomes a refuge from the absurdity and violence of the regime. The images that emerged not only portray life in the barracks, but already hint at the need to understand the environment through ironic distance.

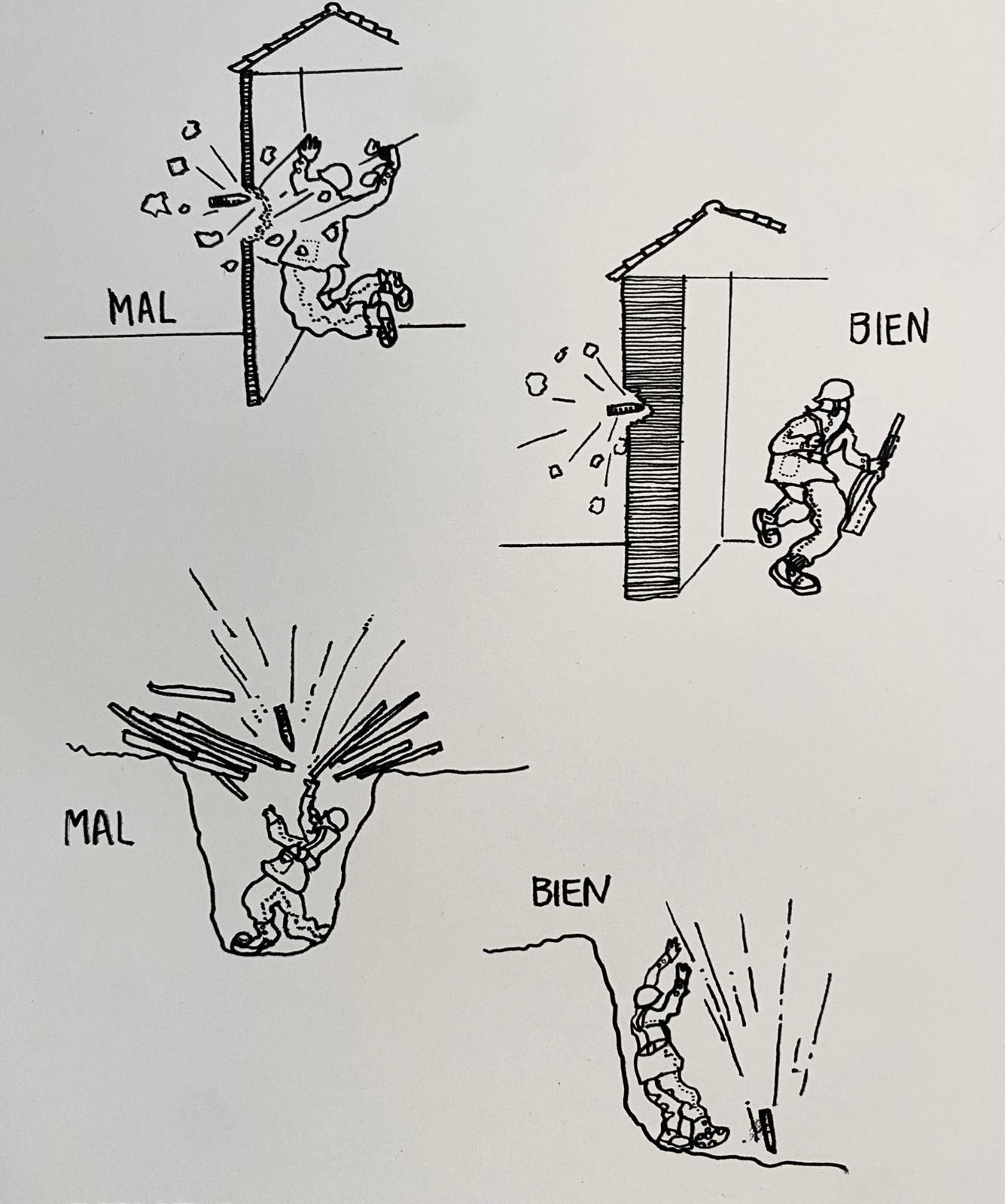

Sèrie Bien/Mal, Antoni Miralda (1966)

Sèrie Bien/Mal, Antoni Miralda (1966)

Once reinstated in the service in 1965, Miralda resumed the thread with Cuaderno de Castillejos, full of drawings and notes made to not listen to the captain and escape, even if only mentally. There, the criticism of the military apparatus takes shape. Added to this are pieces such as Bien/Mal, a series in which he manipulates vignettes from military manuals to highlight their absurd logic. These are works that function as a hot study on power, imposed normality and the desire to stand up.

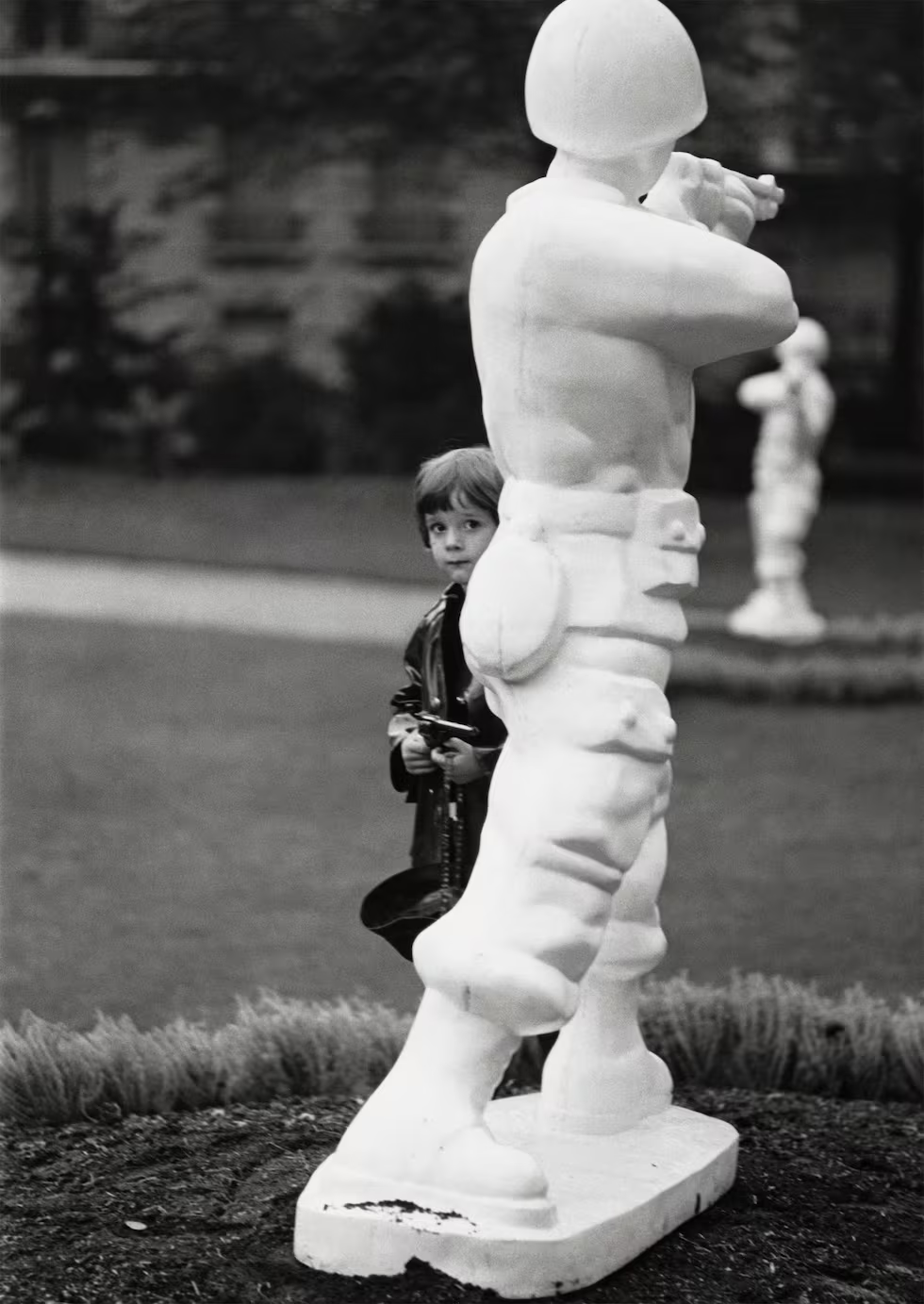

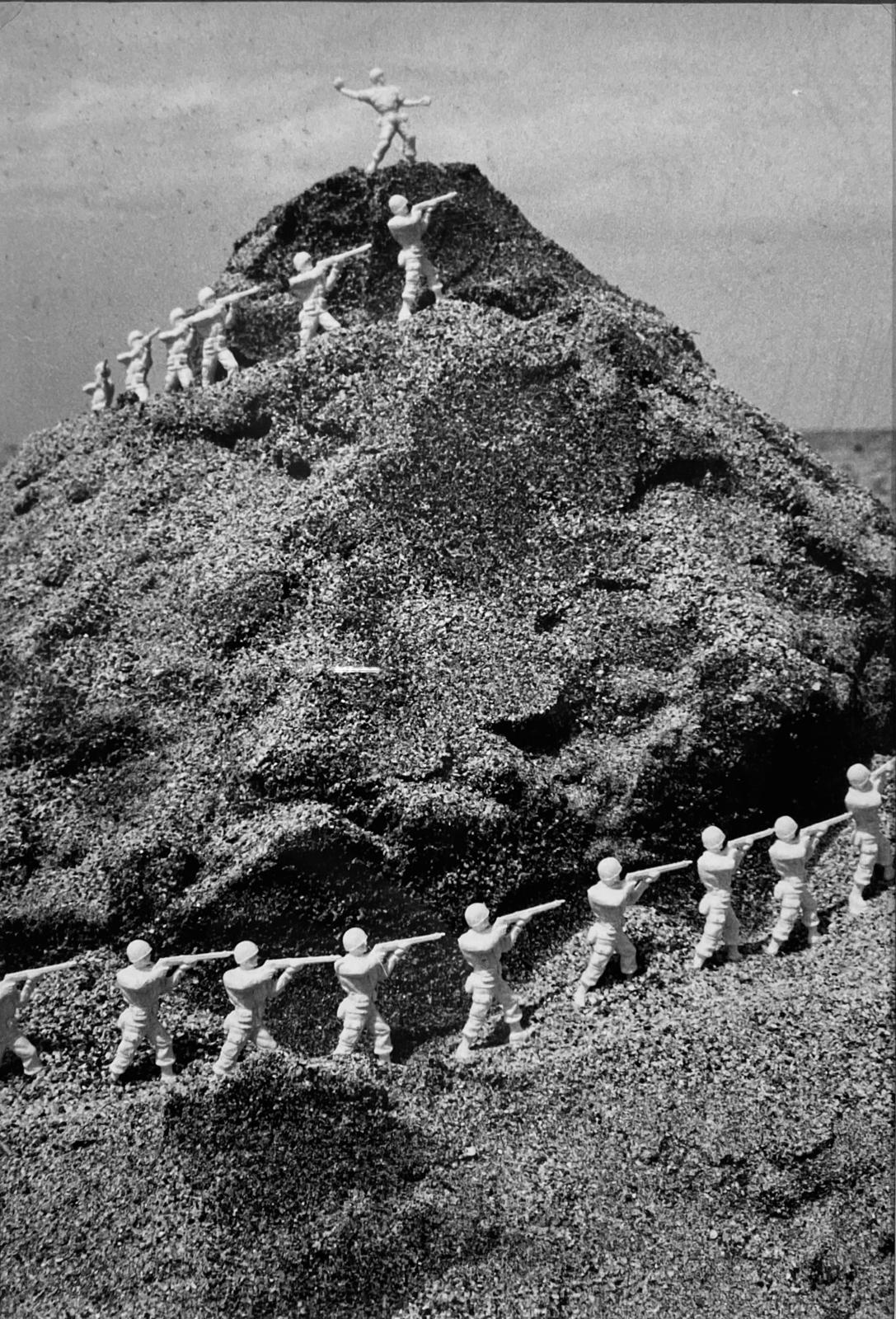

The idea of the soldier as a figure that traverses spaces and discourses reappears forcefully in Soldats Soldés (1967), which was first presented at the Galerie Zunini in Paris. Here, the traditional green soldier is whitened —literally— and becomes a neutral figure that spreads to every corner. It is a kind of presence that contaminates everything, but no longer with the force of authority but with a critical, camouflaged and constant attitude.

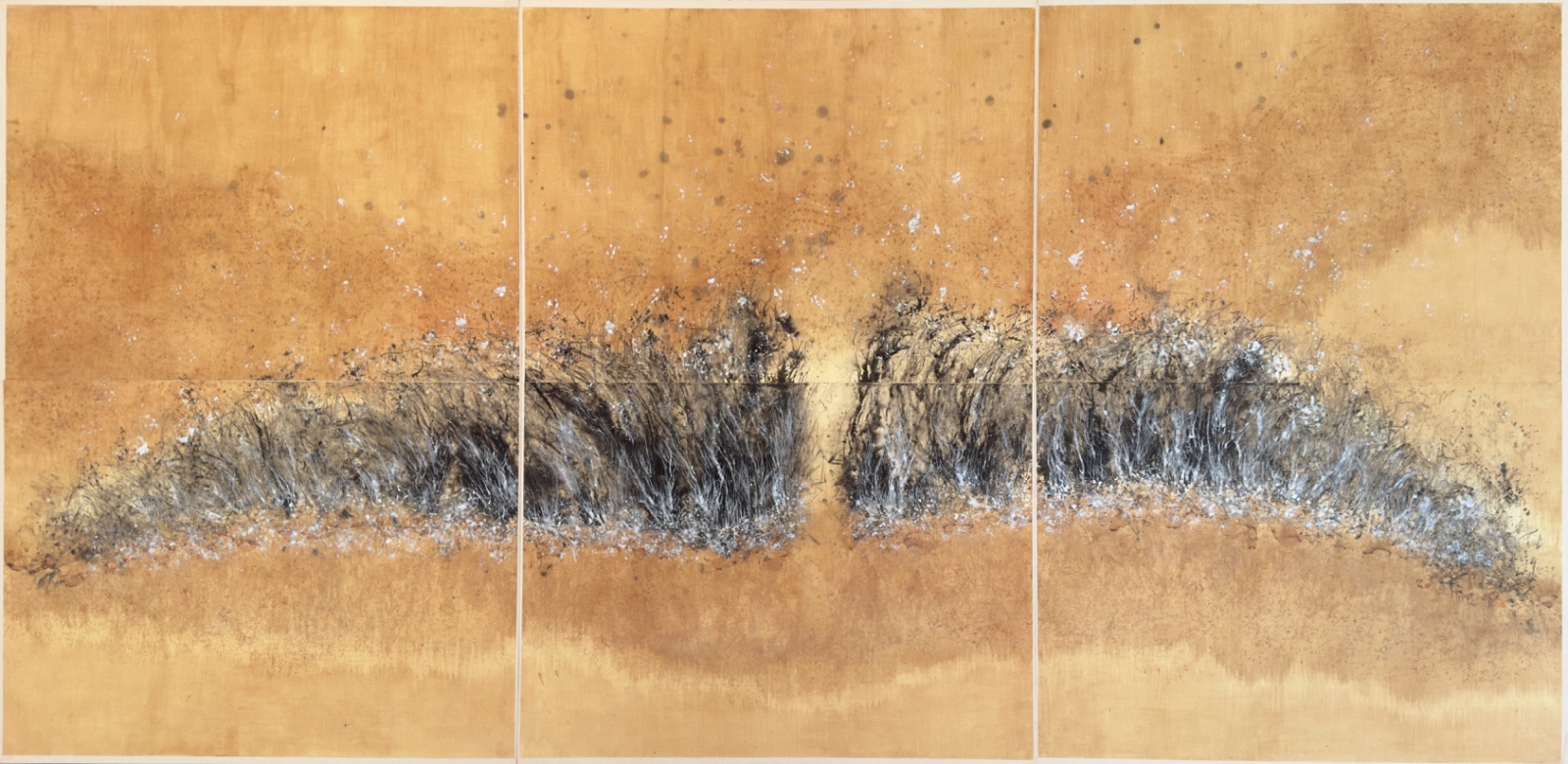

Platja de Còrsega, Antoni Miralda (1969)

Platja de Còrsega, Antoni Miralda (1969)

We also find the sculptures of the Toile de Jouy series, an intervention on furniture and everyday objects, where a troop of white soldiers invades the domestic space. With this gesture, Miralda questions the way in which military iconography has filtered into our daily lives. This line of work is completed with the series Hazañas bélicas, photographs that capture these symbolic occupations, always with a touch of irony, as if the artist were proposing to "improve" the landscape. One of the most iconic moments of the project is when the life-size white soldier takes to the streets of Paris. This journey, filmed together with Benet Rossell, ends up becoming Paris, La Cumparsita (1972), an audiovisual piece that is halfway between performance and experimental cinema.

All in all, what Miralda proposes with BOOOM is an acid reflection on war, power and memory. The little soldiers become a way of looking at the world, of asking ourselves what surrounds us and why. And yes, perhaps it is also, in a way, a tribute to the soldier as a victim of a system that turns him into a piece of machinery that never stops.

The book BOOOM 1962–1972, in addition to collecting all this material, includes texts that help to understand the artist's creative process and the validity of his proposal. Because, despite the years, talk of soldiers, defense and speeches of force is unfortunately once again on everyone's lips. And in this context, Miralda's attitude —that desire to be against, to question what they want us to pass off as normal— continues to be necessary.