Exhibitions

Bernardí Roig and the metamorphoses of Goya's head

“And if the characters in the Trauerspiel die, it is because they can only access the allegorical homeland in this way, as corpses. It is not because they are immortal that they die, but because they are corpses.” Walter Benjamin. Origin of German Tragic Drama (1928)

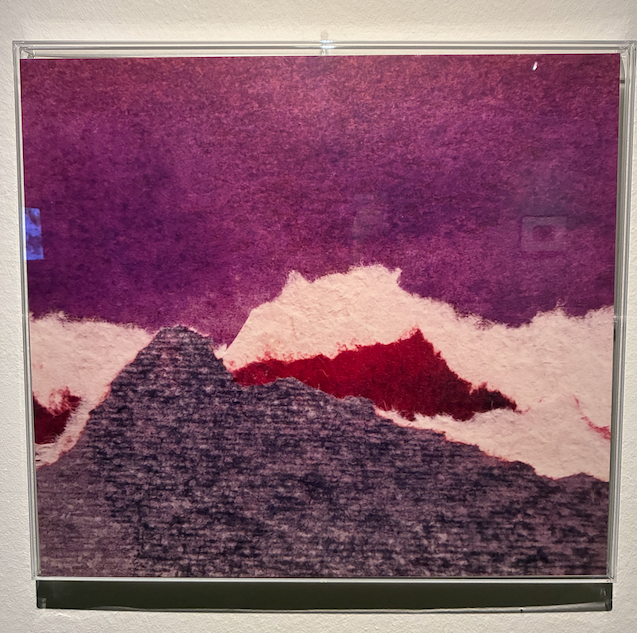

Bernardí Roig surprises us with his conceptual and formal versatility and his multifaceted personality. But no less so with his reflection on art, its history, and its various forms of expression. In his work, history is understood as a consensual fiction. It makes no difference whether the gaze is directed toward archaeology or contemporary art. The essential features that define his work are perhaps memory, time, and identity, concepts he explores through sculpture, photography, video, and multimedia installation. He confronts the representation of the human body as a space for reflection on the individual and society, a relationship that is always uneasy in an increasingly globalized world in which the individual—and, by extension, the artist—counts less and less at all levels.

This is a theme he has masterfully explored when confronting busts from Roman imperial sculpture, where the absence of a nose dominates portraits—a sculptural narrative he unfolded at the National Archaeological Museum of Madrid. The series on Goya's Head also stems from an absence. Goya (1746-1828) died in exile in Bordeaux. In 1888, the Spanish consul in that city decided to exhume the body and send the remains to Madrid. Upon opening the tomb, the shocking discovery was that the skeleton had no skull. Someone had stolen it, and it was lost forever. Obsessed with this fraudulent decapitation, Bernardí Roig undertook the challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic of creating a daily drawing of Goya's missing head, driven by the prominence that the intensity of death acquired during those days. The result is 55 drawings in which the ghost of Goya reappears, as do the turbulences of his era. The tragic Spain between the Baroque and Romantic periods is revealed through a critical lens that can only be expressed through the grotesque. His obsession with Goya goes back a long way. His first steps in art involved discovering the Black Paintings at the Quinta del Sordo, which also resonate in this account of the posthumous decapitation of the painter from Fuendetodos.

The whole series has a trace of metamorphosis, as happens with Kafka or with the German sculptor Franz Xaver Messerschmidt (1736-1783), a contemporary of Goya, who with his series of busts that exemplify characters from facial expressions exaggerated by mental problems, especially paranoia and hallucinations, borders, like Goya, on madness from a theatrical point of view, which links him to the baroque soul.

Goya's skull presides over this tormented mental vanitas of the artist, who seeks, through Goya, his identity and self-portrait. What is art for Bernardí Roig?: "An amalgamation of skins that my head has expelled." If he weren't a Mallorcan artist, we might say that with this work on Goya's head he could pass for an Aragonese artist.

In contrast to this tragic Baroque vision, in the video La joie de vivre , a pictorial theme by Picasso and Matisse, recorded and projected in the rooms of the Tabacalera in Madrid in 2018, five girls run naked through rooms and corridors, happy to display their bodies and their palpitations. Marcel Duchamp would have dedicated to them the Dada aphorism “abominable abdominal furs”, which he published in issue 5 of Littérature in 1919.