Opinion

Rehearse being happy

The social imperative to always be happy, no matter where, how, and at what cost, ends up biting its own tail in one of the most depressing and dark times for humanity. Do we know how to be happy without consuming? Can we be happy in digital isolation? How much does it cost to be happy today? BOG25 adopts the curatorial axis "Essays on Happiness," embracing these questions and energizing its perspective not only through the inclusion of a verb, but also through its dual interpretation: to try, to experiment, to delve deeper, to reflect, and also taking a well-deserved break from the mournful Colombian narrative focused on historical violence.

The exploration of future scenarios less marked by pain also doesn't seek to adopt a simplistic or escapist approach, as Elkin Rubiano, a member of the curatorial committee, tells us: “Happiness today is something problematic in itself. Surveys appear indicating which is the happiest country in the world, and Colombia ranked first in that category a few years ago; but this was more of a promotional effort, because the indicators they took into account didn't measure happiness, but rather joy, which is a spontaneous moment, while happiness is more closely linked to notions of well-being. In fact, the happiness index is called the subjective well-being index, and Colombia, on that index, ranks below half of the rest of the world.”

John Gerrard, Surrender (Flag), 2023.

In order to encompass a city as complex as Bogotá (8,000,000 inhabitants and 1,800 square kilometers) with a history of migrations that accentuate social stratifications, merging the rural and the urban in the peripheries (perhaps in search of happiness), the dynamically proposed curatorial project also allows for the articulation of three public calls in the categories of Neighborhood Art Interventions, Independent Art Curatorships, and Popular Art, in addition to being executed in several sub-lines to delve into multiple possibilities of the concept of happiness: Enjoyment and Leisure addresses collective action, carnival, and play; Ritual and Nature examines artificial paradises, new perceptions, altered states, and healing processes; Stratigraphies analyzes segregation and endogamy in a city divided by socioeconomic strata; Tierra Fría focuses on Bogotá as a frozen city in a tropical country, investigating its ecosystem. The Promise views Bogotá as a place of welcome and aspiration for a better life, and finally, Toxic Optimism critically reviews self-help literature, the business associated with the current imperative to be happy through shopping, books, formulas, and clicks.

Budgets, projections and possibilities

“Biennials are also exercises in exploring the conditions of possibility,” reflects Jose Roca (international advisor to the Curatorial Committee), and continues: “There are very few biennials in the world (...) where there are no limits, but most biennials have to play with contingencies, possibilities, negotiations, budget ceilings, the precariousness of institutions and the temporalities of their staff.” Because “The worst thing that can happen to a biennial is never to happen again. What do you call a biennial of which only one version was made?” Roca asks. That's why they accepted the challenge of not having the traditional preparation times and being able to ensure two versions under this administration and articulate it with other cultural revitalization efforts, since this BOG25 is inseparable from the International Festival of Living Arts, which will also take place biennially in even-numbered years.

Organized by the Mayor's Office of Bogotá through the Secretariat of Culture, Recreation, and Sports, BOG25 has an investment of approximately €1,500,000, projects the mobilization of 60,000 spectators, and the creation of more than 1,500 direct and indirect jobs in the capital, activating at least 30 public and cultural spaces.

This political desire almost reads like a desire to foster a cultural habitus that would energize a kind of internal social and cultural GPS in Bogotá, allowing populations unaccustomed to aesthetic reflection to navigate the world of art and culture, perhaps contributing to happiness, seeking to reduce stress, increasing confidence, and extracting pleasure and a sense of belonging from these challenging experiences.

Alfredo Jaar, Studies on Happiness, 1980-1981, Chile.

Biennials as dynamic spaces of speculation

In the Colombian context, BOG25 marks a milestone and an evolution in art biennials. “Many people believe that if international artists are invited to a national event it's to gain an audience, visibility, or because they're trendy artists,” says Jaime Cerón , a member of the curatorial committee, “but they're almost always involved because they generate intrinsic dialogues with local artistic practice and complement what's already happening with certain notable efforts in Bogotá, such as the Luis Caballero Prize, established in 1996 and focused on established artists of different ages, which has already reached its 12th edition in 2025.”

“In a broader context, what is a biennial?” asks Jose Roca. “What is it for? Who is it aimed at? (...) A biennial is also a space for speculation. It's not a group exhibition where one takes a theme and articulates that theme with the relationship between the works, which is what independent curators generally do. (...) A biennial is more like launching a series of concerns, collecting things, putting them in relation, but always understanding that this is always in flight,” another energetic verb to describe a project that seeks to energize an apparatus as complex and pachydermic as a biennial can be.

Beatriz González, The Happiness of Pablo Leyva, 1977. © Nicolás Jacob. Courtesy of Casas Riegner.

Between consensus and risk.

Regarding the risks and advantages of collective curation, Roca tells us: “...there's a huge diversity of perspectives here. We met every week to propose artists, practices, or sometimes works that interested us, and then we voted with the sole condition of not voting on the same proposals someone else had brought.” “I think biennials are a space where you can take risks,” Jaime Cerón chimes in, “to experiment, to take a risk that might not be the most common approach and open up the possibility of ups and downs; that exposes the public to a more complex universe.” Roca continues: “...the problem with consensus is that it kills radicalism, and generally speaking, very radical proposals don't advance when there are consensual curatorships. So we also gave ourselves a rule: each of us could have one or two wild cards, where we would say, "I'm going for this practice," and no one could say no. So, you could really bet on an artist you considered to be truly important.”

From these discussions emerged a powerful list with a deck of established and new names such as Johan Samboní, John Gerrard, Ángela Teuta (whose proposal for the Luis Caballero award is articulated to the tour), Iván Argote, Rejane Cantoni, Alejandro Tobón, Museo Aero Solar, among others, and of course Alfredo Jaar and Beatriz Gonzalez.

Congratulations from Jaar and González

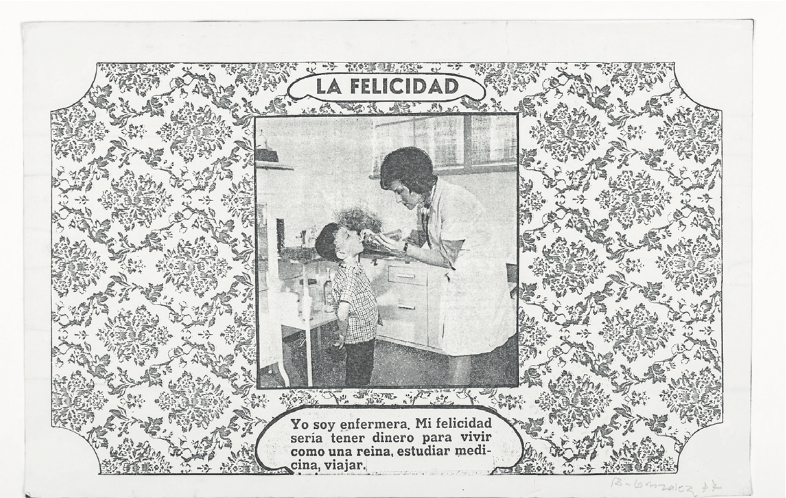

As historical references of Latin American art from the late 1970s and early 1980s, the works of González and Jaar are central to this biennial, as they critically explored the notion of happiness, highlighting contextual tensions and complexities. Beatriz González (Colombia, b. 1938) is an artist who fuses the country's political and social history with popular culture and the media through the appropriation of journalistic and media images, transforming them into paintings, furniture, or installations that question representation and collective memory (Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá, n.d.). His series "The Happiness of Pablo Leyva" (1977), one of the curatorial committee's references, questions happiness in a critical manner, by exploring the contradictions inherent to this notion in the Colombian context of the time, exposing the superficiality of certain ideals of happiness and inviting a reflection on the construction and social consumption of this emotion, and how the political and social tensions of a country can influence its perception (González, 1977).

Alfredo Jaar (Chile, b. 1956) is an artist, architect, and filmmaker whose work focuses on the relationship between art and geopolitics, addressing themes of social injustice, armed conflict, and the portrayal of violence in the media. His work is distinguished by documentary research and the creation of installations that confront the viewer with realities (Guggenheim, n.d.). Jaar's public intervention "¿Es usted feliz?" (1979) in Santiago de Chile, which also serves as a reference for BOG25, was an action that challenged citizens by distributing plastic bags with the question "Are you happy?" in public space, forcing individual and collective reflection on emotional state during a time of military repression. This work explored the tensions between imposed or expected happiness and the reality of an environment under duress, questioning the nature of happiness under adverse political conditions and the ability to freely declare it (Jaar, 1979). In Bogotá, Jaar's work will be presented on billboards, in public spaces, and even during halftime at the soccer stadium, seeking, as Elkin Rubiano says, "to make the question 'Are you happy?' float in the air."

Beatriz González, Anonymous Auras, 2007–2009. Installation in four columbariums at Bogotá's central cemetery.

Possible futures

At this point, it's pertinent to ask: what will remain for the Bogotá ecosystem at the end of BOG25? Biennials like Venice, art fairs like Art Basel Miami, and mega-events like MANIFESTA Barcelona have received criticism for their recovery of spaces that are initially intended to be cultural, but later prioritize commercial processes, and for allocating large budgets to events that don't always energize the artistic or cultural ecosystem that hosts them. The first to answer is Jose Roca, who bluntly states: "In a country like Colombia, any money invested in culture is one less peso going to war, so everything spent on culture is well spent, basically as a matter of principle." Rubiano adds: " A large part of the public that will be attending this Biennial are students from public schools, and this is very important: that they can access a cultural offering not mediated exclusively by entertainment."

When asked how they imagine BOG31 in six years, Cerón believes that the ideal would be "a biennial that is already institutionalized and has greater autonomy." Roca hopes that "it will be well-established for its quality and will be one of the benchmark biennials in the region, with a very robust educational project that will be developed during the years when there is no biennial." For his part, Rubiano hopes that the biennial will be like Rock al Parque (the largest free, open-air public rock festival in Latin America), which turned 30, because "it ended up professionalizing the bands, developing complex stage setups, professionalizing sound engineers and music producers. In other words, this will end up having an impact on the creation, circulation, and production of the sector."

Autonomous, institutionalized, rooted, high-quality, and impactful: Desirable adjectives for a biennial, or for our everyday happiness. It doesn't matter. Both are ventures. Both are a decision: To take a risk. To experiment. To be.