reports

Marta Palau, the forgotten artist of the Catalan Republican exile, returns home.

She is one of the most innovative artists born in Catalonia in artistic practices and who most challenges our contemporary times and, however, except for the exhibition at La Lonja de Zaragoza (2014) and the Museo Morera (2015), her work has not received the recognition it deserves until today, when the Museo Tàpies, starting on February 27, will put an end to the long "exile" of Marta Palau (Albesa 1934-Mexico City 2022).

"My mother arrived in Mexico in 1940 at the age of six with nothing and without knowing how to speak Spanish," says the artist's daughter, Marta Gassol, in good Catalan from Tijuana. "My grandfather Francesc," she continues, "had studied in Salamanca during Unamuno's time, was a doctor and a CNT councilor stationed at a hospital in Terrassa, and, at the end of the Civil War, he was able to escape from labor camps in Spain and France before securing passage to America and, in the short time, claiming his family. Needless to say, their lives were in mortal danger in Albesa."

Marta Palau and her sister Teresa, at the time of their exile.

On January 8, 1940, thanks to the aid of the Junta de Ayuda a los Republicanos Españolas (JARE) and the one hundred dollars sent by Francesc Palau, Antònia Bosch and her two daughters, Marta and Teresa, boarded the Italian ship Vulcania in Lisbon, bound for New York. "From there," says Marta Gassol, "they had to make the road trip to Nuevo Laredo. Republican solidarity, especially from an exiled friend from Madrid, and from the government of Lázaro Cárdenas, helped them start a new life in Mexico growing tomatoes and cotton and pursuing a medical career. "My mother married Albert, a doctor, like my maternal grandfather, and son of Ventura Gassol. The former advisor to the Generalitat (Catalan government) lived in Switzerland and was an excellent person. He was proud of having been the world's first Minister of Culture and of having saved so many people during the war."

Marta Gassol recalls that, once they settled in Tijuana, her maternal grandfather, with the memory of the Civil War fresh in his mind, joked about the convenience of living on the border "just in case." "Tijuana," she continues, "reminded them of their homeland. The Mediterranean climate, the mountains, the sea, the vineyards." Being born among peasants and being the daughter of Republican exile left a lasting mark on her mother. She experienced exile as a wound, but also as a source of creativity that prompted her to seek a means of resistance within her Catalan and Mexican roots.

Marta Palau and Ventura Gassol.

Marta Gassol portrays her mother as a tireless worker who practiced all forms of art: printmaking, painting, sculpture, ceramics, installation, and tapestry. In Mexico, she studied painting with another exiled artist, Bartolí, and in the 1960s, tapestry with Josep Grau Garriga in Barcelona. Palau was one of the most important artists of contemporary Mexico, both for her technical innovation and the symbolic depth of her work. Her art, deeply connected to natural materials—such as branches, henequen, corn husks, jute, ixtle, roots, clay, cork, and glass—refers to a magical and ritual dimension that engages with indigenous worldviews. But her discourse goes beyond the aesthetic: her installations and sculptures contain an incisive critique of borders as a symbol of repression, a defense of migration, and a sharp analysis of the violence inflicted on bodies, especially women's bodies.

Palau challenged patriarchal canons of art and dared to depict female sexual desire (The Waterfall, which can evoke a gigantic cascade of sperm and the creation of life) in a time and cultural context where these themes were taboo. Her work invites us to reflect on migrants seeking a better future in the United States. The experience of exile allowed her to deeply empathize with the experiences of those fleeing their countries of origin due to violence, poverty, or persecution. In this sense, her work not only reflects on the past but directly addresses the present. "If in prehistory, waves of migration flowed from North to South, now they follow the opposite path," says her daughter.

Marta Palau, Double Wall, 2006.

Trump's policies, which intensify mass deportations and encourage the criminalization of migrants and hate speech, resonate like a dark echo in Palacio's artistic practice. Her pieces invite us to reconsider the border not as a boundary, but as a space of interaction and transformation. Borders not only divide, but are also spaces where struggles for dignity and human rights are waged.

Marta Gassol, a gynecologist in Tijuana, highlights an immense burlap vagina titled Ilerda, a nod to her mother's birthplace and the fertilizing power of nature. Or the installation Doble Mur, seven rows of dry branches, simulating a precarious ladder, the fragile rungs barely connected, surrounding the silhouette of a person lying on the ground, like the plaster silhouettes drawn by the police. "It is," says Marta Gassol, "a reminder of the migrant who died at the border, a peasant whose only land is the one covered by his mat, and who, when he dies, is buried with it." At the same time, these ladders can serve to overcome physical and political barriers or access a higher level of consciousness. "She," says her daughter, "not only created works, but universes, woven symbols that connected human stories with the earth, cultural roots, and the spiritual."

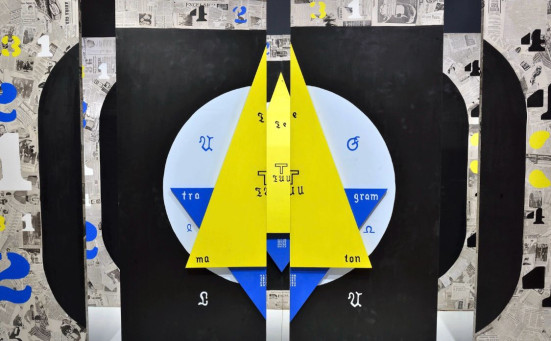

Marta Palau, Alchemical Setting, 1970. Amparo Museum

At the same time, Marta Palau explores the transformative dimension of manual labor, forgotten by industrial societies, and reclaims textile techniques and natural materials to recover the dignity of work traditionally associated with women, such as weaving, knot-tying, and embroidery. The artist addresses the representation of women as symbols of a profoundly earthly and ancestral connection with nature and the cosmos: women as naualli (enchantress or magician), as creators, as transformative and metamorphosing powers, women who weave bare threads like fibers of life. "She said she was a naualli, the powerful, magical, creative hand, caretaker of the tribe, shamanic"; that is, art as a mediator between the material and the spiritual and a space of resistance," emphasizes her daughter, who will be present at the opening of the exhibition "My Paths Are Earthly," curated by Imma Prieto, director of the Museo Tàpies, in collaboration with the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (MUAC).

Marta Palau, Ilerda V, 1973. MUAC