Exhibitions

Kerry James Marshall, black is a color

“What is the color black?” is the rhetorical question that accompanies us through the rooms of the great exhibition of the American artist Kerry James Marshall, open until January 18, in the most emblematic rooms of the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

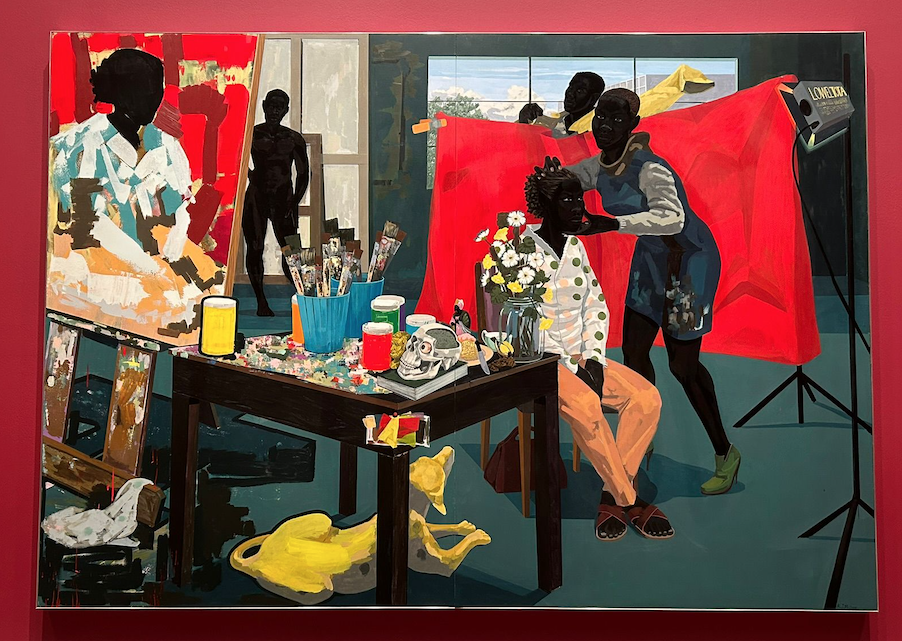

The space is conceived with the same intention as the works that inhabit it. On the red, green, and blue walls—colors that, when mixed, give rise to what Marshall calls chromatic black —a pictorial strategy unfolds where the multiplication of dark pigments not only constructs the black figure against an equally black background, but also questions the visual and symbolic hierarchies that have historically defined representation.

The exhibition brings together eleven cycles spanning forty-five years of artistic practice. Each testifies to Marshall's deliberate break with abstraction and his commitment to figuration as a way to rewrite art history from within. His visual foundations were formed, in part, through comics and the absence of heroic Black figures in mainstream visual culture. From this lack emerged, in 1999, Rhythm Master , his own narrative universe, conceived as a space of representation for African American youth.

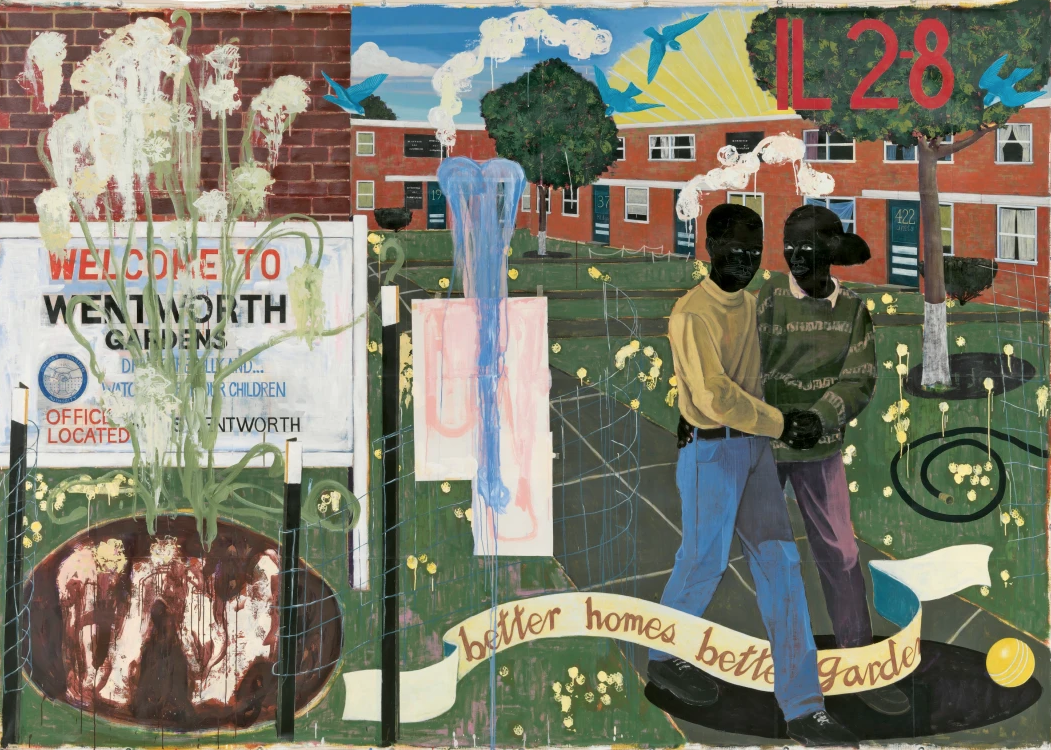

Later, Marshall places the Black figure at the very heart of the pictorial tradition, with the ambition that his work engage in dialogue with that of masters like Manet, Delacroix, and Velázquez. The absence of subjects resembling him in the most celebrated genres of Western painting prompts him to rewrite its conventions, also imagining how a pictorial Afrofuturism might manifest itself. In the allegory of coexistence represented in the Garden Project series, which occupies gallery 3, Marshall draws a line of continuity between Giorgione's Concerto Campestre (c. 1510) and Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863), to underscore the contrast between the idealized representation of the European garden and the Garden Projects of Chicago. In this shift, the artist reveals the distance between the utopia imagined by some and the social reality experienced by others.

Marshall centers the Black figure as a subject in its own right: beautiful, elegant, and fully autonomous, transcending the function of a body to which political symbolism is attached. Each room is a reencounter with something we think we have seen, but which, in the face of his work, compels us to look twice. In The Invisible Man (1993), inspired by Ralph Ellison's novel, Marshall explores the tension between invisibility and visibility: through the use of ivory, chromatic, and Martian black, he constructs the figure and the space of an illuminated interior, where the subject's presence observes us with clarity and distance, aware of the paradox of being seen through the paint that simultaneously conceals him. This strategy is revisited in the Pantheon series, shown in gallery 4, where figures who spearheaded slavery during their presidencies, such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, are depicted in a comical and diminished manner, contrasted with the grandeur of the color black that dominates the room, affirming the centrality and dignity of Black culture in visual history.

In the final room, Red, Green and Black , the exhibition closes with what could be interpreted as a celebration of Black nationalism, evoking the colors of the UNIA (Universal Negro Improvement Association) and the Pan-African flag created by Marcus Garvey in 1920. However, Marshall's question remains insistent: “What is the color black?” beyond contemporary political associations. Here, the artist positions the Black body—both female and male—with an erotic charge that directly engages with the nudes of masters like Titian and Goya, reclaiming the beauty of these bodies beyond any symbolic or political value. By employing the colors of the flag, Marshall introduces a touch of humor that shifts the focus away from historical facts and places these figures at the center of the narrative, even above the movements that surround them.

Ultimately, Marshall invites us to contemplate the color black for what it is: just another color, or perhaps the only possible color.